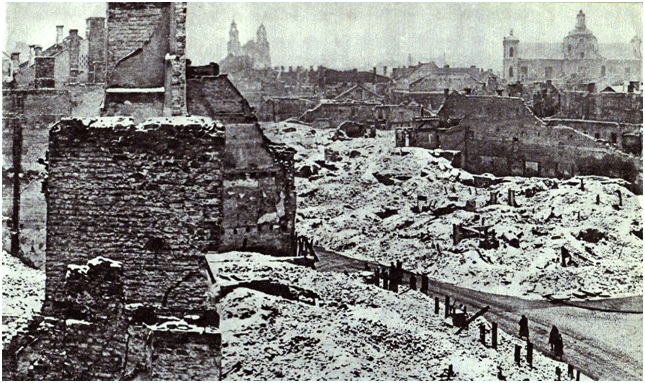

Vocal Varshe, a group of musicians from Poland, performed songs in Hebrew, Yiddish and Ladino at the site of the former Great Synagogue in Vilnius, destroyed after World War II, on the evening of June 6, 2018. The event was organized by the Polish Institute in Vilnius and the Lithuanian Jewish Community. The Polish musicians from Warsaw performed songs from the Warsaw and Vilnius ghettos.

LJC executive director Renaldas Vaisbrodas began the event with the poem Vilne by Moshe Kulbak.

Vilnius mayor Remigijus Šimašius greeted the audience and said the concert venue reminded the public, Polish and Lithuanian residents of Vilnius, that more could have been done to save Jews from the Holocaust. He also called for an appropriate commemoration at the site, whether that be partial reconstruction of the synagogue or some other form, to remind future generations of what happened. He said this would serve to unite the different ethnic communities in Vilnius.

LJC chairwoman Faina Kukliansky thanked the musicians for coming and performing and the Vilnius mayor who granted permission for the concert at the site infused with the spirit of the teachings of the Vilna Gaon.