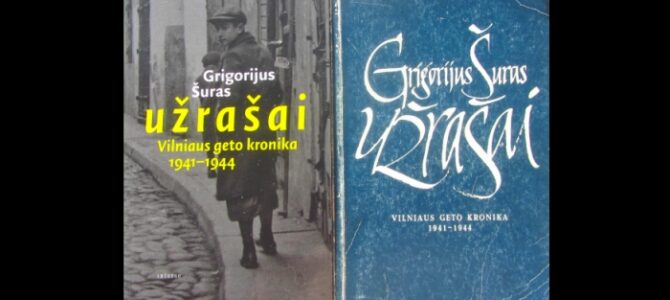

Grigoriy Shur’s Vilnius ghetto diary has been reissued with support from the Goodwill Foundation, with a new cover and new introduction.

Perhaps the most informative of the several Vilnius ghetto diaries, Shur’s manuscript was originally published in Lithuanian translation by the Era publishing house in Vilnius in 1997 with partial funding from the Lithuanian Culture Ministry, and was roundly ignored by the general public.

The new edition is the same translation published by Era back in 1997 by Nijolė Kvaraciejūtė and Algimantas Antanavičius. It contains the same introduction by Pranas Morkus and forward by Vladimir Porudominsky, but adds a new and short introduction by the writer Vytautas Toleikis, who surveys recent Holocaust literature published in Lithuanian, including his keen observations about the book “Mūsiškai” [Our People] by Rūta Vanagaitė and Efraim Zuroff, or more precisely, how Lithuanian nationalists responded to it. Here’s a rough translation of part of Toleikis’s introduction:

“Unfortunately, the situation is hardly simpler than when the first edition was published. The international repercussions and the disproportionate public reaction following the appearance in 2016 of Rūta Vanagaitė and Efraim Zuroff’s book ‘Mūsiškai’ [Our People] seems to have pushed us back twenty years. It seems as if the attempt is again being made to fool the public, to convince people that collaborations with the Nazis wasn’t all that bad, that the thirst for freedom for the home country by acquiescing to the Nazi occupiers made it permissible to condemn to death a portion of the country’s citizens, to divide up their property, even to excuse partially those who murdered Jews: if not for the Germans, it never would have happened… The war of commemorative plaques in Vilnius testifies to this.

“I think the second edition of Shur’s ‘Entries’ has appeared just in time. … his ‘Entries’ are not just an individual chronicle of the catastrophe of the Vilner Jews but perhaps the most objective one, attempting to convey the big picture, avoiding personal digressions, as if from the eyes of everyone who ended up in the ghetto. This is like a prologue-compendium of history, a beginner’s textbook on the history of the Vilna ghetto.”

While Hermann Kruk’s Vilna ghetto chronicle is much longer, Kruk was basically an outsider, a Polish Jew who had fled from Poland proper, from Warsaw, to Vilnius along with so many others, while Shur knows the location, the streets and buildings, were the event he records took place, and his sense of place, of the local geography, is immediately recognizable by Vilnius residents as the one they share, although they might have born many decades later. Kruk’s extensive chronicle written more like newspaper articles than diary entries does have the distinct advantage, however, of being written in Kruk’s native Yiddish.

Sources close to Shur manuscript and the translation effort back in the 1990s said Shur wrote in Russian although he was a native speaker of Yiddish. They also said he wasn’t fluent in Russian and there were some passages which didn’t make complete grammatical sense to the translators, and so were skipped. Why Shur felt he had to write in Russian rather than his native Yiddish is an object of speculation. Most of the speculation is that he foresaw a Soviet victory against the Nazis, although he didn’t survive to see it.

The first edition published back in 1997 had problems with the glued binding so that pages began falling out after just a few full readings. The new edition is made of sturdier paper and glue with a shiny color cover, augments by a full section of color and black-and-white photographs near the end. The new edition keeps Shur’s diary alive, but still inaccessible for most Holocaust scholars, being in Lithuanian. At some point this “most objective” chronicle of the Vilna ghetto should be translated to English, preferably using the original manuscript in Russian with some textual analysis of the apparently ungrammatical passages by people with accurate knowledge of his mother language and the history of Vilnius and Jewish Vilna.

The second edition of Shur’s diary in Lithuanian is available from knygos.lt or directly from the Goodwill Foundation.