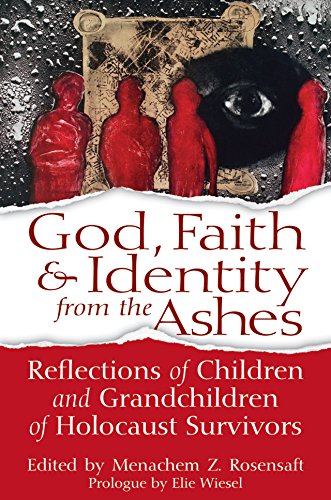

God, Faith & Identity from the Ashes: Reflections of Children and Grandchildren of Holocaust Survivors

Menachem Z Rosensaft, Editor, Elie Wiesel, Prologue by

In this important and poignant collection of thoughts and memories from descendants of Holocaust survivors, 88 men and women from around the world share personal, often heartrending reflections. As their parents and grandparents age and pass away, these adults remember the palpable darkness and shadows of fear that haunted them. Contributors were asked “how their parents’ or grandparents’ experiences and examples helped shape their own identities and their attitudes toward God, faith, Judaism, the Jewish people, and society as a whole.” The answers, some short, others longer, are all brutally honest. Whereas some found faith and a spark of hope amid the carnage, others lost religion entirely, and still others lament how similar tragedies could unfold in the aftermath of “never again.” Readers may shed tears of sorrow, but will be inspired by the strength and courage of this worthy volume. Elie Wiesel contributes a prologue.

What did I inherit from my family who survived the Lithuanian Holocaust?

by Faina Kukliansky

What did I inherit from my family who survived the Lithuanian Holocaust? Surely not silver knives and forks. Nor did I inherit Sabbath candlesticks from my mother’s parents. They were Ríve and Hirsh-Tsvi Taube from the Lithuanian town of Šiauliai, called Shavl in Yiddish.

My grandmother Ríve was extremely beautiful, with smooth and black hair, light blue eyes and fair skin. My children and grandchildren inherited my grandmother’s eyes. They are electric blue.

It was my grandmother Ríve who saved my mother Klara, known as Kéylke, during the operation to exterminate the children in the Šiauliai, or Shávler, ghetto, it was she who ended up in the Stutthof concentration camp with three daughters, and it was she who pulled her gold fillings out of her own mouth and sold them to save her children. It was she who came back to Šiauliai, but with only two daughters, Kéylke and Básye – the third was buried at Stutthof. She came back because she hoped to find her only son, unaware that he had been killed fighting the Nazis as a soldier in the Soviet army.

My maternal grandparents, who died while Lithuania was still under Soviet rule, prayed to the Most High until the last day of their lives, heedless of the atheism surrounding them. They were buried in the traditional way, mit di takhríkhim (in shrouds). I don't know why, after all the horrors, they still believed in the Most High. Perhaps because not all of their children were murdered, they believed that the Most High had taken pity on them…

Nor did I inherit silver candlesticks from my paternal grandparents, Saulas (Shéyel) Kukliansky, a pharmacist and chemical engineer, and Zísele Kukliansky, a medical doctor, in the city of Veisiejai near the Polish-Lituanian border. Although they were highly educated, they did not observe Jewish traditions and did not attend synagogue, but, of course, they did have a set of silver candlesticks at home. In that respect, most Jewish homes were alike.

The war began for my father, Samuelis (Shmuel) Kukliansky, in 1941 when he was ten and was bombed by the Germans at his Communist youth movement camp in western Lithuania. Quickly identifed as a Jewish child, he was forced to clean the homes of murdered Jews.

After a long, difficult search, my grandparents found their youngest child and returned with him to Veisiejai, but they were only together again for a brief time before my grandmother Zísele was grabbed off the street by her Lithuanian neighbors, locked up, and killed. Her murderers probably included some of her own patients. My father was guilt-ridden for the rest of his life, believing that my grandparents’ extended search for him had prevented the family from leaving Lithuania in time. He somehow blamed himself for his mother's murder.

My grandfather Saulas was left with three children. Despite being physically weak and traumatized by the murder of his beloved wife, he did not break down. Late one cold, rainy night in the autumn of 1941, he led his children out of Veisiejai. The next day all of the city’s Jews were shot.

The Kukliansky family's wanderings had only just begun. On foot, they managed to get to the Belarusian city of Grodno. They then fled the Grodno Ghetto just before its liquidation and survived the remainder of the Nazi occupation in a cramped pit deep in a forest. My father spent his adolescence underground, knowing that his mother, grandparents, cousins and all of his school friends had been murdered. In that pit, my grandfather Saulas taught the children geography, mathematics and literature, and sang them opera arias every day.

From that time onward there has been no Most High in the Kukliansky family. I believe my father's brother is one of only a few Jews in all of Israel today who refuses to hang a mezuzah on his door. Their God died with the murder of their mother.

I ask myself, what have we, the children of the survivors, inherited beyond the pain?

We inherited the names of murdered family members, but they were changed so that they would not sound Jewish. The war had ended, but we still had to hide the fact that we were Jews. We competed to see whose name was less Jewish. In our family, Azriel became Azalia, Jonah became Eugenius, Feygele-Tsipóyre became Faina (me), and Zísele became Zinaida. After all, we were born in the Soviet Union where our parents, after accidentally surviving the war, were not supposed to be Jewish any longer. We were supposed to be Soviet citizens, a kind of "ethnic" identity.

We inherited the terrifying fear of war. From our childhood onward, this fear was our identity, the expression of our Jewishness. The grown-ups didn't stop talking about their memories in our presence. They did not tell their children what had happened to them, but they spoke about it all among themselves, and we drank it all in: fear hovered everywhere around us, as if our parents’ awful reminiscences had been events in our own lives. Maybe that was why we became just as traumatized as they were.

When grandmother Ríve was in her advanced years, she always used to yell to me: "Feytske (the diminutive form of my name), hide! The children's Aktion is beginning, hide!" [An “Aktion” meant the mass deportation and killing of Jews in the Nazi ghettos]. Before we went to sleep at night, we used to ask our parents, "Will there be war?" Only after we were told “no” could the light be extinguished and we could fall asleep.

I inherited Jewishness, and pride in my people. Despite the misfortunes of war, the post-war Soviet anti-Semitism and all the restrictions on freedom in the Soviet Union, in our family we were taught to be proud that we were Jews.

When we were children, they did not tell us that Lithuanians had murdered Jews. It is only now that I am able to fully reflect on the environment in which we grew up. Anti-Semitic propaganda was rabid before and during the war, and contributed to the extermination of more than 200,000 Lithuanian Jews, to Lithuanians looting Jewish property, to their entering Jewish homes and dividing up and selling clothes ripped from corpses, never mind stealing jewelry and paintings. What reasons were there to make them love us more after the war?

The Soviet occupation also continued the fascist anti-Semitic propaganda, and no one told us the truth about the mass murder of Jews. The Soviets even blew up the monument which Vilna Ghetto survivors erected at their own expense at Ponár (Paneriai), outside Vilnius, one of the larger Jewish mass murder sites in Europe, and erected a different one with a Soviet star in its place.

We were proud to identify as Jews, even if that didn't help our careers. When I was seven, I had to tell a children's library employee I was a Jew in order to fill out my reader's form properly. Soviet propaganda and our parents' fate are what turned me into a Zionist. I remember clearly the Six-Day War, when the Israeli "aggressors" rapidly won the war against all the Arab states. My entire athletic team refused to talk to me because I was "one of those."

I truly inherited a folkloric type of Jewishness. There was no end to singing and jokes in my mother's family, even after all the misfortunes of war. Heedless of all the troubles and comparisons of "life before the war" versus "life after the war," my mother's family preserved authentic Jewish folklore. My mother still has a blue notebook with songs from the Shávler Ghetto. Everyone sang them regularly. As a child, I never learned any other songs. Only those.

I loved being with my grandmother. Sometimes it was tragicomic: I still hear her words ringing in my ears: "Kéylke, do you remember how she lost the key in the ghetto and we couldn't go home? Oh that was funny. And remember that sweater I knitted? It was so beautiful. Now who gave me the old wool? That winter when we were in the Kafkaz [name of a section of the Šiauliai ghetto], it was so warm thanks to that sweater. And do you recall Avrémke who died during the children's Aktion? He knew so well how to make people laugh. His mother, poor thing, she couldn't endure it, she couldn't survive his death. And remember that little joke, 'Kumt Meyshke Blékher, macht dem gelékhter, ' [Yiddish semi-rhyme for, “Here comes Meyshke Blecher and makes a joke….”] That was real fun…"

And they used to laugh, the sisters Básye and Kéylke and grandmother Ríve. But grandfather Hirsh never laughed. Instead he checked, "Is everyone home? Are we all together?" And then he'd make sure the door was latched.

I inherited the desire to learn, to strive to achieve the unachievable, not to be part of the crowd, to make independent decisions, sometimes in opposition to the great majority, and to fight against despair. Benedict de Spinoza wrote that that which must take place will of necessity take place. For my parents, Spinoza, who sometimes acted and thought differently from his entire community, was a role model. Do not be cattle driven to their death, even if a spiritual leader wants to lead you there. My parents and grandparents did everything they could to stay alive and to give the gift of life to their children. That is their heroism.

So I have inherited a faith in life and the future. It could not have happened any other way…