by Borukh Gorin, lechaim.ru

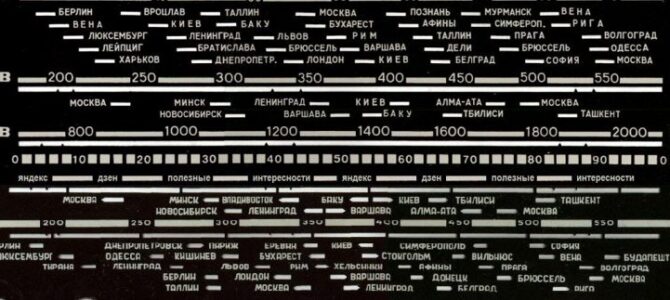

It was the early 1980s. On the coffee table stood a VEF-202–heavy, solid, with the smell of plastic and Soviet electronics. Its long antenna, like a taut nerve, caught the voices of a distant world. On the dial–London, Paris, Monte Carlo, and between them the frequencies that carried what was absent from Soviet news: the BBC, Voice of America, Radio Liberty.

There was a whole world on shortwave. On Kol Israel, I listened to Jewish music–old songs that seemed somehow familiar and distant at the same time. On the BBC, Seva Novgorodtsev talked about Western music, which we only knew about from rare records copied onto reels. And Svoboda talked about things that our newspapers were silent about. About Jews in the USSR, who “don’t exist.” About refuseniks, who are not allowed to leave. About synagogues that are still standing, but people are afraid to come to them.

And there was also a religious program.

I listened to Rabbi Haskelevich. I always listened alone.

This voice, breaking through the howl of jammers, sounded confident, a little muffled, with a characteristic intonation in which one could hear erudition, irony, and slight irritation at the same time – as if he was not just broadcasting, but talking to someone who should not be interrupted.

He talked about the Torah, about holidays, about traditions, about the life of Jews in that world that was not written about in our textbooks. He talked about something that seemed almost underground at the time.

In everyday life, such words were not spoken about me. At school, they did not talk about it. At home, although we were a very Jewish family, we talked about it carefully. But Haskelevich spoke loudly.

And each time he returned to one story.

1927. The arrest of the Lubavitcher Rebbe.

He talked about that night arrest, about prison, interrogations, about how the death sentence was commuted to exile, about the miracle of liberation.

I listened. And it was not just a story.

It was a voice from the distant past, breaking through into my quiet Soviet evening. He spoke as if all this was happening not sometime in Leningrad, but here and now.

Then the years passed. The Soviet Union disappeared. Shortwaves became useless to everyone. And one day I met Rabbi Haskelevich in person.

I expected to see a sage. Majestic. Confident.

But I saw a not very exalted person.

A little eccentric, a little funny. He spoke quickly, jumping from topic to topic, as if he were still speaking through interference.

He waved his hand, forgot where he started, got his words mixed up.

I listened to him and understood: that voice from the air was something more than just a person.

It was a symbol, a myth.

And in front of me sat just a friend.

“Well, lechaim!”

I nodded.

Some legends are better left on shortwave.