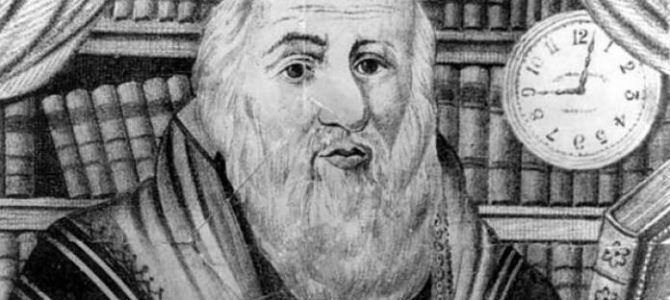

Eliyahu ben Shelomoh Zalman

(Gaon of Vilna; 1720–1797), Torah scholar, kabbalist, and communal leader. The Gaon of Vilna (known also by the acronym Gra, for Gaon Rabbi Eliyahu) was a spiritual giant, a role model and source of inspiration for generations, and the central cultural figure of Lithuanian Jewry. Eliyahu ben Shelomoh Zalman was born into a rabbinical and scholarly family, and following a short period of study in a heder, studied Torah with his father. At age 7, he was sent to study with Mosheh Margoliot, rabbi of Keydan (Lith., Kėdainiai). Soon thereafter, he began to study on his own, and at 18, left Vilna to go into “exile”—a period of wandering through Jewish communities of Poland and Germany.

Upon Eliyahu’s return to Vilna, he shut himself in his house and devoted his energy to Torah study. He continued in this path throughout his life, supported by the local Jewish community. When Eliyahu was 35 years old, Yonatan Eybeschütz, who was suspected of Sabbatian leanings, turned to him, seeking support and referring to him as “one who is unique, saintly, holy, and pure, the light of Israel, possessing all-embracing knowledge, sharp and well-versed, with 10 measures of esoteric knowledge . . . whose praise is recognized in all of Poland . . .” (Eybeschütz, Luḥot ha-‘edut [1756], p. 71). It seems, then, that the Gaon of Vilna had already achieved legendary status during his lifetime.

Gaon of Vilna held no official office, and served neither as a communal rabbi, judge, nor head of a yeshiva. His standing and authority can best be explained with the help of the designation given to him by his disciples and admirers: “ha-Gaon he-Ḥasid” (the genius, the saint). The term gaon recognized his extraordinary achievements in the study of Torah. His learning encompassed all fields of Torah: the Written Law and the Oral Law, both the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds, the Tosefta’, halakhic midrashim, and works of commentators to the Talmud and of halakhic codifiers. In addition, he mastered kabbalistic literature.

The Gaon’s scholarship was extraordinary from a qualitative perspective as well. He recoiled from any demonstration of intellectual acuity as a goal in its own right; instead, he was uncompromising in striving to discover the true meaning of a text. Following the pattern of medieval commentators, he raised questions about the correct reading of Talmudic texts. Rather than deciding between various extant readings, he daringly proposed emendations wherever an existing text appeared faulty. Owing to his fluency in the entire corpus of Talmudic literature, he was able to support his emendations with parallels found elsewhere in rabbinic literature.

The designation “Ḥasid” that was also attached to the Gaon honored his moral virtues and mystical qualities. A striking expression of his piety was seen in his severely ascetic lifestyle, entailing his nearly total abstention from worldly affairs and frivolous social contact. The Gaon maintained that avoiding communication was a prophylactic measure to prevent interpersonal transgressions, and that abstention from worldly affairs allowed him to devote time and effort to the service of God, first and foremost, and to the study of Torah. The Gaon’s piety was also expressed in his attitude toward mysticism. He not only mastered kabbalistic literature but also described personal rare and sublime mystical experiences, encompassing migrations of the soul and revelations of magidim (angelic teachers).

Even though the Gaon generally refrained from involvement in communal affairs, two instances caused him to veer from this pattern. The first involved a quarrel between the Vilna community and its rabbi, Shemu’el ben Avigdor. The controversy began in the beginning of the 1760s and centered on control of communal institutions and sources of revenue. Here the Gaon joined those who opposed the city’s rabbi, after having been persuaded that the rabbi violated the commandments of the Torah and conducted himself in a morally objectionable manner. The parties to the conflict turned to Polish authorities, whose intervention led to the imprisonment of a number of Jews, including the Gaon.

The Gaon is also famous for his role in the struggle against Hasidism. In the late 1760s and the early 1770s, he heard testimony on deviant conduct of people associated with the new Hasidism founded by the Ba‘al Shem Tov. Hasidim were accused of unruly behavior during prayer, of altering prayer texts, and of establishing new prayer groups, thus disassociating themselves from existing synagogues. They were also accused of sinning by neglecting Torah study and of hunting for recruits to their movement among young students. The Gaon particularly condemned three practices: (1) Hasidim were said to turn somersaults prior to prayer, an act of self-abasement that they claimed brought a person to modesty and humility; the Gaon, however, viewed the practice as idolatrous; (2) Hasidim were said to scorn Torah scholars (the Talmud refers to one who scorns Torah scholars as a heretic); and (3) he held that a new, Hasidic interpretation of a passage in the Zohar was a grave perversion of the meaning of the text.

Based on these testimonies, the Gaon concluded that Hasidim fell into the category of heretics. Following this ruling, he and the leaders of the Vilna community assembled for an emergency meeting during the intermediate days of Passover 1772, and declared war on Hasidism. Some important Jewish communities answered the call of the Vilna leadership and joined the struggle. It is important to emphasize that this was not merely a conceptual debate. The Vilna community and others that joined it availed themselves of coercive and punitive measures available to them to suppress Hasidim and to seek to eradicate the movement. The organized struggle continued for about three decades.

It is difficult to imagine that the Gaon would have decided to fight Hasidism had it not been for the traumatic memory of the Sabbatian movement’s turning into an antinomian sect. More than anything else, he acted under the terrible impression left by the struggle with the Frankists in the 1750s. The Gaon viewed the new Hasidism as an extension of the Sabbatian heresy, and he was determined to fight it to the end. It is not surprising, then, that he totally rejected the attempts by Hasidic leaders to discuss their differences. But the Gaon’s resolute position and the immense authority that he enjoyed throughout Lithuania precluded any possibility of compromise between the Hasidim and their opponents, the Misnagdim, during his lifetime.

Viewed in historical perspective, the Gaon’s battle against Hasidism was a failure. Not only did Hasidism not disappear, but in the last third of the eighteenth century it gained strength and continued to spread to new areas of Eastern Europe. In the next generation, Ḥayim of Volozhin, the Gaon’s leading disciple, openly admitted that the Hasidim were not heretics and reconfigured the struggle against them as a conceptual and educational one.

In some writings of nineteenth-century maskilim in Eastern Europe, the Gaon is described as a harbinger of the Haskalah. This assertion is based on his positive attitude toward the study of sciences, on criticisms that he leveled against the educational system, and on the fact that he wrote books on geometry and Hebrew grammar. The assertion does not, however, stand up to critical analysis. The Vilna Gaon’s views on science did not, in effect, veer from what was accepted among the traditional scholarly elite. He maintained that such study was vital for a proper understanding of various halakhic issues. As opposed to the maskilim, he assigned no independent value to such study.

The Gaon’s criticism of the educational system also linked him to the outlook of scholars of previous generations—first and foremost that of Maharal of Prague. And the “books” the Gaon wrote on geometry and grammar were but notes that he had taken for personal use, rather than works that were intended to spread knowledge. The image of the Gaon as the harbinger of Enlightenment tells us more about the enormous authority that he enjoyed during the nineteenth century—and the need of maskilim to attach themselves to such authority—than about his actual positions.

The Vilna Gaon’s books were published posthumously. They include commentaries and emendations to the Bible, the Mishnah, Midrash, the Shulḥan ‘arukh, and to several classic kabbalistic texts: Tikune Zohar, Sefer yetsirah, and Sifra’ di-tseni‘uta. The Gaon’s works on geometry and grammar were also published. But his influence did not result from the dissemination of his writings. More than anything else, it was the Gaon’s image as symbol and example of exceptional excellence in Torah study that established his position in the collective consciousness. As such, the Vilna Gaon continues to serve as a source of inspiration and example.

Suggested Reading

Joseph Avivi, Kabalat ha-Gera: Gilui Eliyahu (Jerusalem, 1992/93); Jacob Israel Dienstag, Rabenu Eliyahu mi-Vilna: Reshimah bibliyografit (New York, 1949); Immanuel Etkes, The Gaon of Vilna: The Man and His Image, trans. Jeffrey M. Green (Berkeley, 2002); Louis Ginzberg, Students, Scholars, and Saints (1928; rpt, Lanham, Md., 1985); Israel Klausner, Vilna bi-tekufat ha-Ga’on ([Jerusalem], 1941/42); Bezalel Landau, Ha-Ga’on he-ḥasid mi-Vilna (Jerusalem, 1966/67).

Author: Immanuel Etkes

Translation: Translated from Hebrew by David Strauss

From the YIVO Open Encyclopedia. Full text here.