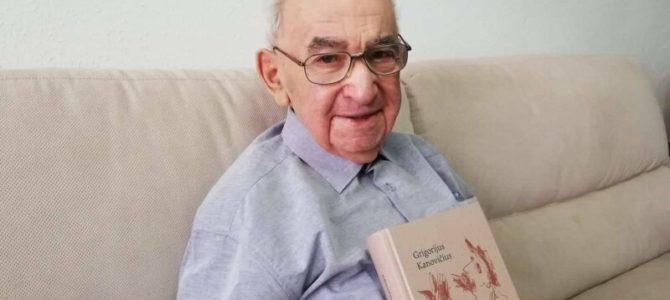

As the Vilnius Book Fair ramps up this year, Grigoriy Kanovitch’s “Miestelio romansas” (the Lithuanian translation of his “Shtetl Love Song”] is reappearing on bookshop shelves. The novel tells the stories of people in small-town Lithuania, including Jews, Lithuanians, Poles and Russians, in the period between 1920 and 1941. Kanovitch’s son Sergejus, also an accomplished author, interviewed him in a press release for the book fair.

How does Shtetl Love Song fit in the context of your entire corupus? How important is it that the Lithuanian edition has gone into its second printing?

Shtetl Love Song is my most personal book. It’s the most biographical. I wouldn’t say I’m spoiled by second editions. Of course there have been some. But I should consider the additional publication of Shtetl Love Song the most important. News of this made me extraordinarily happy.

What do you feel now that you’ve stopped writing when your work is published again?

After I’ve stopped writing now, I consider the second printing of Shtetl Love Song my farewell to my profession.

Do you regret stopping after Shtetl Love Song?

No, I do not regret it. I don’t want to repeat myself. And I don’t want to write more poorly.

What might change your decision to stop writing?

Youth.

What would you write about again?

About the same thing.

How do you explain the popularity of “Miestelio romansas” in Lithuania?

We all have roots. We don’t appear out of nowhere. Farms, church villages, towns and shtetls were our origin and the cradle and source of extremely gifted and extraordinarily interesting people and characters.

Lithuania is marking the anniversary of the Gaon. What should be told to people who do not know of the Gaon and his teaching?

It seems to me not just the Gaon should be remembered. The worshipers should be remembered, too. They are no longer here. Fate so decreed that I became the first chairman of the postwar Lithuanian Jewish Community. Of a community which continually sank and is sinking. I think today, as the former chairman of this Community, that, unfortunately and no matter how painful it is to me, it does not have a long future.

What role do intellectuals play in discussions of historical justice?

The role of those who consider themselves intellectuals in discussions of the not-very-nice historical truth is great: it is dishonorable to avoid these kinds of discussions. The truth heals.

When nothing material remains of an ethnos undergoing extinction, what does remain?

Memory remains. It has to remain.

Can love heal hatred towards one’s neighbor?

Yes. Only with love and truth can one prevail over hatred.

Uri the Rabbi, one of the characters in your novels, says: “the homeland of all of us is memory. And here we all are, living in it.” How do we get along in the blood memory left behind, now that those who shed their blood are gone, how do we love one another in this bloody shadow?

In spite of all circumstances, a person must love the other person. Maybe that’s the moment when a person remains a human being. There is no other remedy. Between hatred and love, one must always choose the latter.

What is a Litvak?

First of all he is a person who is a patriot who loves the Lithuanian land and sky.

Would you like to return to prewar Jonava? If so, why?

Yes, I would like to return to prewar Jonava. To where I was happy.

Choose a title for our talk.

The truth heals.

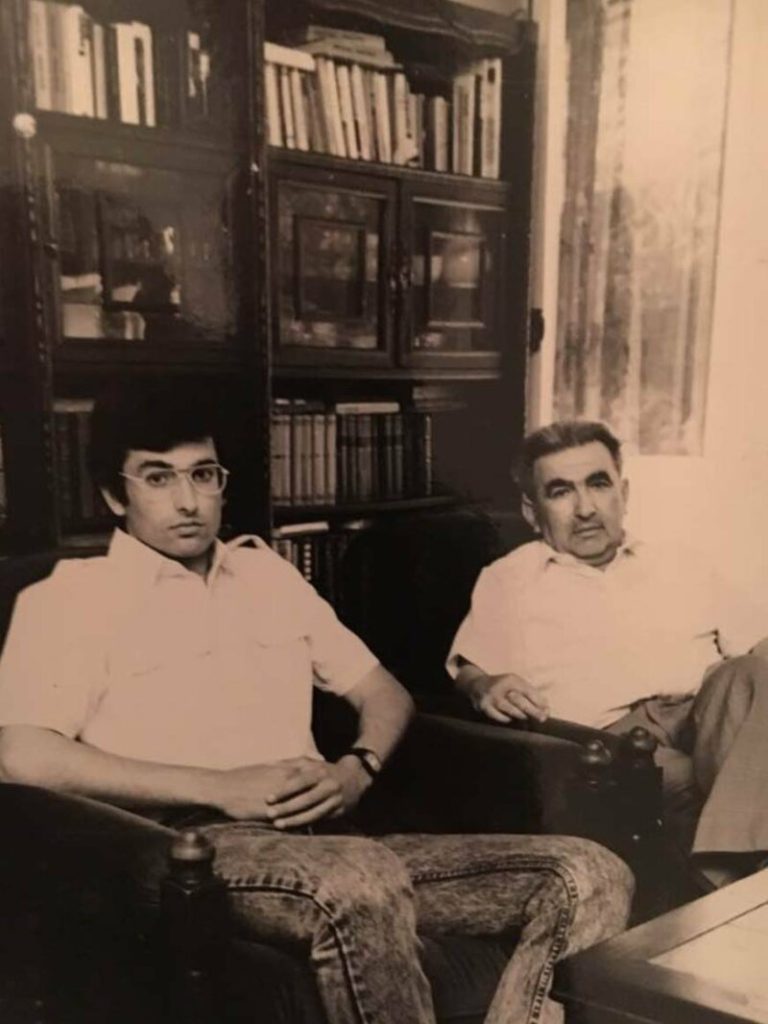

Sergejus and Grigoriy Kanovitch