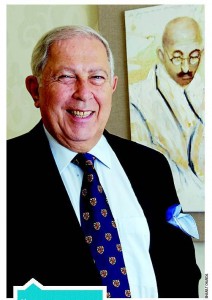

Presentation by Yusuf Hamied, FRS, chairman, Cipla Ltd., India, July 11, 2019

Presentation by Yusuf Hamied, FRS, chairman, Cipla Ltd., India, July 11, 2019

I am privileged to address this audience and to share with you some features of my life’s work. It is an occasion I will cherish and treasure for the rest of my life. I am an ordinary person, neither an academic, an outstanding chemist or a leading scientist. At an early stage in my life, I met an exceptional individual, a past President of the Royal Society, Lord Alexander Todd, who forever changed the course of my life. In 1953, a chance meeting during one of his visits to India, led to an opportunity for me to study Natural Sciences at Cambridge University from 1954 for 6 years. During 1957 to 1960, under his tutelage, I did research in natural product chemistry, “Structure of the Aphid pigments”. It was the first time that the new methodology of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) was applied to determine the structures of large organic molecules. Lord Todd was my teacher, guide, mentor, friend and advised me throughout the important stages of my career until his demise in 1997.

I returned to India, armed with a PhD in chemistry and embarked on a career spanning 6 decades in the global pharma industry. During this period, my major contribution was the adaptation and implementation of the chemistry that I had learnt in this country. This led to my maintaining a strong and close scientific and industrial bond with Britain.

An Indian philosopher, Swami Vivekananda, once said, “Wisdom lies not in the amount of knowledge acquired but in the degree of its application”. The application of one’s knowledge, specifically in areas where one has expertise is essential to contribute to the betterment of society. This is one of the prime objectives of the Royal Society.

The pharma industry is different from other industries. We have to combine business acumen with a humanitarian responsibility. We are the custodians of healthcare and are responsible for the welfare and treatment of patients to overcome disease and lead a better quality of life. Two major factors essentially control the industry – monopoly, arising out of intellectual property rights, which gives product exclusivity to the inventor and the high rate of obsolescence of drugs. Newer medicines have to be constantly invented to enable long term progress, sustainability and stability.

In 1960, healthcare in India was in its infancy. The situation for indigenous pharma companies was bleak. Multinational companies were dominant and controlled the market. There was very little basic manufacture, intellectual property rights were controlled by the stringent British Patent Act, 1911. At all times, one had to navigate carefully the interface between science and commerce, as well as cope with innumerable political barriers.

The foundation and backbone of the pharma industry is the availability of quality, active pharmaceutical ingredients. This led to my early involvement in drug research with the main objective of making essential drugs required in the country using patent, non-infringing processes. This R&D falls under the heading “repurposing and repositioning”. In scientific terminology, it means incremental innovation in products and processes that are already known and established. It includes applied research on pro-drugs, metabolites, chiral drugs, liposomal drugs, co-crystals, newer polymorphs, nano-particles, enhancers, boosters, drug combinations, newer devices, newer routes of administration and delivery systems. It is appropriate technology which is scientifically sound, relevant, adaptable to local needs and using available resources. This is the very basis for self-reliance and self-sufficiency, much needed not only in emerging and developing countries but globally.

In 1961, we challenged our Indian government to change the existing patent laws covering monopoly. We succeeded in 1972 after an 11 year struggle. The patent act was modified essentially in 3 need based critical areas – health, food and agriculture. No longer could one monopolize the end product, but only the process to make it. Since then, I have been directly instrumental in developing the synthesis of a large number of important drugs using novel processes. As there were no patent laws in India and as our pharma industry is highly secretive, my team and I seldom patented or published our in-house intellectual scientific work.

The1970’s and 1980’s were most productive as with no drug monopoly, we were able to produce by newer technologies, a wide spectrum of essential drugs for a variety of diseases ranging from malaria to cancer. The drugs reversed engineered included propranolol, mebendazole, fluconazole, alendronate, ciprofloxacin, Tenofovir, imatinib, fluticasone to name a few. This opened the path for us to expand globally, exporting essentially to Africa, Europe and the USA.

Another major interest of mine in the 1970’s was respiratory disease. We pioneered for the first time in India, the development of metered and dry powder inhalers for asthma. This initiative required the production of effective bronchodilators, the leading one at that time being salbutamol. The original synthesis involved starting from acetophenone and had two hazardous steps, chloromethylation and bromination. We started our process from readily available inexpensive methyl salicylate and the key innovative feature was avoiding the above hazards and using a new reducing reagent that did 3 different reductions in one step. Till today, this industrial synthesis is still being followed.

Since the early 1990’s and to date I have also been fully committed to the fight against infectious diseases, most notably HIV/AIDS, essentially in Africa. The syntheses of all the then available antiretroviral drugs, Zidovudine, Lamivudine, Stavudine and Nevirapine were extremely difficult. I was instrumental in reverse-engineering these, developing newer routes of synthesis, make them in large quantities and also cost effective. In the year 2000, we repositioned the latter three drugs into one fixed dose combination tablet, Triomune, taken twice a day as against 12 individual tablets taken throughout the day. The separate tablets collectively were available at that time for $12000 per patient per year. On a humanitarian basis, we offered the world’s first WHO approved combination drug to control HIV at below $1per day. At that time, only a few thousand could afford treatment in Africa and there were 8000 deaths due to HIV per day. Today, due to this pioneering effort, over 17 million in Africa alone are being treated. HIV is no longer a death sentence, the stigma associated with it has been contained and survival rates are extremely high. The price of the most advanced 3 drug combination today is below 20 cents per day,$70 per year in Africa, most supplied from India, whereas similar drugs in the USA are available for over $24000 per year. This humanitarian initiative has already saved millions of lives in Africa and is ongoing.

India joined WTO in 1995 and brought back product patents in 2005.We once again entered into a monopoly environment in healthcare. Today there are many newer issues in healthcare-Anti-microbial resistance, resistant TB, widespread cancer, etc. apart from epidemics such as Ebola and Zika. These are being tackled at many levels by governments, pharma companies, universities and the medical profession.

My own role in the coming years will also involve a closer examination of 5 new technologies that are already revolutionizing healthcare-3D, artificial intelligence, digitalization, automation, flow chemistry and continuous manufacture. For some time, Medical science has been shifting from chemistry to biology. We therefore need to rethink, redesign and rebuild a fresh approach to tackle the ongoing problems of healthcare.

My mantra in life has been to provide access to affordable medicines and that none should be denied medication. The disease profile in the emerging countries is frightening and is in continuous crisis. We need newer, adaptable technologies to prioritize healthcare, and create a world where every citizen can dream of a decent quality of life.

Success is not a destination, it is the quality of the journey. Success does not lead to greatness, what really matters is one’s contribution towards the moral and social obligations to society and improving the lives of our fellowmen. For me, the past 60 years has been a difficult struggle against many odds. Today, this recognition from the Royal Society is the fulfillment of my life’s mission.

Thank you