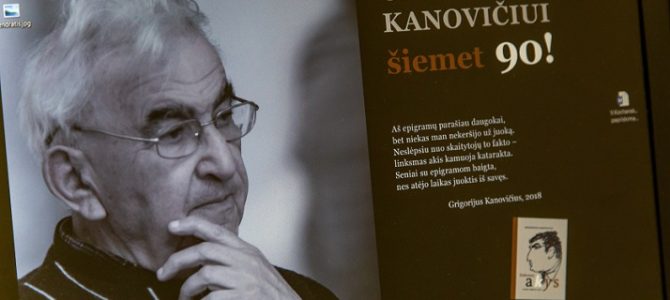

by Sergejus Kanovičius

My father wrote “Shtetl Love Song” at the age of 84. And he promised himself he wouldn’t write more: “it’s better I not write, and I don’t want to write more poorly.” Over the last six years his books have been translated to and published in English, German and Macedonian. They are being translated now as well, and soon more will appear. No matter how my brother and I have tried to provoke Father to write more, he firmly keeps to the promise he made to himself. Not a month goes by that he doesn’t get a letter from publishers or journalists asking for interviews, to attend a book launch or to travel to deliver a lecture. Very rarely he agrees to answer questions in writing: “I have said everything already, I have written everything, let them read my books.”

It’s not the first time when his name is heard at the bustle of the book fair, when his selected writings are presented, Rūta Oginskaitė’s memoir biography “Gib a Kuk” [Take a Look] and now “Linksmos Akys” [Happy Eyes]. But the author is not at the book fair. And he won’t be at the next one, although there might be a different book. If not at the Lithuanian book fair, then maybe the German, Polish or English. As I recall Father never liked answering questions about his work. It seemed incomprehensible to him how an author could also interpret that which he has created, and he didn’t understand either how one could explain what one has experienced and given birth to. Just take me and read. Father doesn’t like questions about his work. Unless those questions are broader, about a worldview. But this is in the books, too.

In this time of commerce and digital marketing the author is forced to become more than an author, he must also be an advertising agent for his own work. This was always foreign to Father. Both then when he could still fly, and now, when he pedals an exercise bicycle and says he is pedaling in order to travel into the past.

Launching a book without the author is a challenge in today’s modern format. Undoubtedly. But no one will introduce the book better than the book itself. When it is read and judged one way or another. Old fashioned? Perhaps. But Dostoyevsky doesn’t appear at exhibits either. Of course there remains unsolved that one required attribute, the autograph. In Father’s case it is always there anyway, the cover will always say “Grigoriy Kanovich.” And when presentations his work happen without him, without him advocating for himself, what is most important remains: the reader’s judgment.

There is another aspect: knowing when to exit the stage. Especially for masters of the word, whether artistic or political. Lingering too long and the attempt to remain on stage at any cost is not just dangerous. It is depressing to see and listen to people who, excuse me, simply talk nonsense. Father would never in his life be able to answer the question: “Dear writer, what did you want to say when you wrote this?”

«Душа больна», пожаловался рабби Ури, и его любимый ученик Ицик Магид вздрогнул.

«Больное время – больные души», мягко, почти льстиво возразил учителю Ицик. «Надо, ребе, лечить время».

«Надо лечить себя», тихо сказал рабби Ури. Он поднялся со стула и подошел к окну, как бы пытаясь на тусклой поверхности стекла разглядеть и себя, и Ицика, и время, и что-то еще такое, неподвластное его старому, но еще цепкому взору. Боже праведный, сколько их было – лекарей времени, сколько их прошло по земле и мимо его окна! А чем все кончилось? Кандалами, плахой, безумием. Нет, время неизлечимо. Каждый должен лечить себя, и, может, только тогда выздоровеет и время.

It’s all written down. All you have to do is read it and try to think. A book written is the author’s child who no longer belongs to him. He wanders and looks for those who will understand him, embrace and protect him. Or not. Everything else is the charming bustle of the market.

Vilnius Book Fair

February 23, 2019

Photos: Laima Penek