On December 4 the Lithuanian Jewish Community hosted a meeting/lecture/discussion and exhibition opening called “Mission: Lithuanian Jewish Citizens. Siberia” dedicated to discussing the deportations from Lithuania in June of 1941. Usually the official accounts of the deportations seem to suppress the multi-ethnic composition of deportees and the diversity of their positions and beliefs. The only thing uniting all the deportees was the fact they were considered undesirable by the new occupational regime.

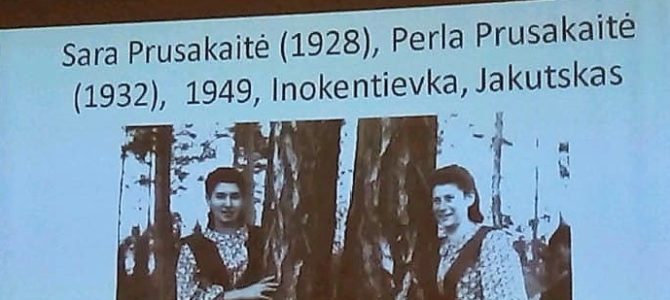

The event was organized by the Vilnius Jewish Public Library and the Jakovas Bunka welfare and support fund. The photographic exhibition contained pictures of graves in Siberia, including those of Jewish, Polish, Russian and Lithuanian deportees. The photos came from the collections of the Lithuanian National Library, the Center for the Research of the Genocide and Resistance of Residents of Lithuania, the photographer Gintautas Alekna and Dalia Kazlauskienė, the widow of photographer Juozas Kazlauskas. The project received support from the Department of Ethnic Minorities under the Lithuanian Government.

LJC board member Daumantas Levas Todesas, Vilnius Jewish Public Library director Žilvinas Beliauskas and Department of Ethnic Minorities director Dr. Vida Montvydaitė spoke to the topic at the event.

Well-known historian specializing in research on the deportations Dr. Violeta Davoliūtė gave a presentation based on her scholarship on the 1941 deportations. She said “the history of Jewish deportees as with the history of Jewish political prisoners in Lithuania and other countries has gone almost unresearched. For many decades the myth created the Nazis and Lithuanian collaborators was promulgated, that the Jews are enemies, the Jews are Bolsheviks who deported Lithuanians to Siberia.” Davoliūtė said this myth and other false accusations dominated even in Soviet times, and “no one in modern independent Lithuania has yet looked more deeply into the false accusations against Jews and tried to negate them. On the contrary, it is supported passively.”

There were about 800 Jews in the Soviet gulags of whom at least 80% died. Of the 2,200 Jews deported at least 20% died. Therefore the number of Jews who died in the gulags and in exile was about 1,100, it was noted. That means Lithuanian Jews suffered proportionally more than any other ethnicity in Lithuania from the deportations. Mainly intellectuals, merchants, industrialists, activists in political movements and leaders of volunteer organizations–people who supported Lithuania’s independence–were exiled.

The destruction of families, deporting them to locations unfit for habitation, causing some of their deaths, is a crime against humanity and an expression of genocide by the occupying power carried out against the people of Lithuania, it was noted.

“The very idea of Jewish deportees has been all but forgotten in Lithuanian society, or at least it has been ignored for the sake of making this a purely ethnic Lithuanian tragedy. Can this interpretation of history change? I believe it is possible. It has to be admitted this subject has been little studied,” Dr. Davoliūtė said.

LJC chairwoman Faina Kukliansky, historian Tomas Balkelis, historian Irina Guzenberg, members of the Community and members of academia participated in the event.