Yitzhak Rudashevski’s Vilnius ghetto diary is one of the most important testimonies to reach us from the Vilnius ghetto, an authentic eye-witness account of history as it happened. The Lithuanian Jewish Community went to extreme efforts to insure the diary finally be published in Lithuanian translation.

“I think my words are written in blood,” the young Rudaashevski wrote in his diary inscribed in school notebooks. After reaching the age of 15 in the ghetto, Rudashevski and his family were murdered in Ponar.

The book launch included a performance by 16-year-old violinist Ugnė Liepa Žuklytė who played Anatolijus Šenderovas’s piece “Cantus in memoriam Jascha Heifetz.”

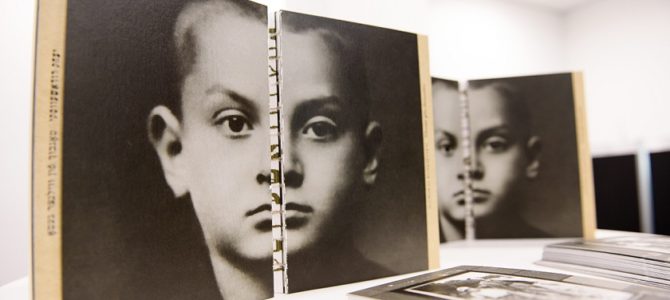

The book was published in both Yiddish and Lithuanian. The cover photograph of Rudashevski is split in two, symbolizing his life cut short.

Mindaugas Kvietkauskas translated the Yiddish manuscript to Lithuanian and student of Yiddish Akvilė Gregoravičiūtė edited the Yiddish component. YIVO in New York, Yad Vashem in Jerusalem and the Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum in Vilnius helped with the project. YIVO conserves the original manuscript.

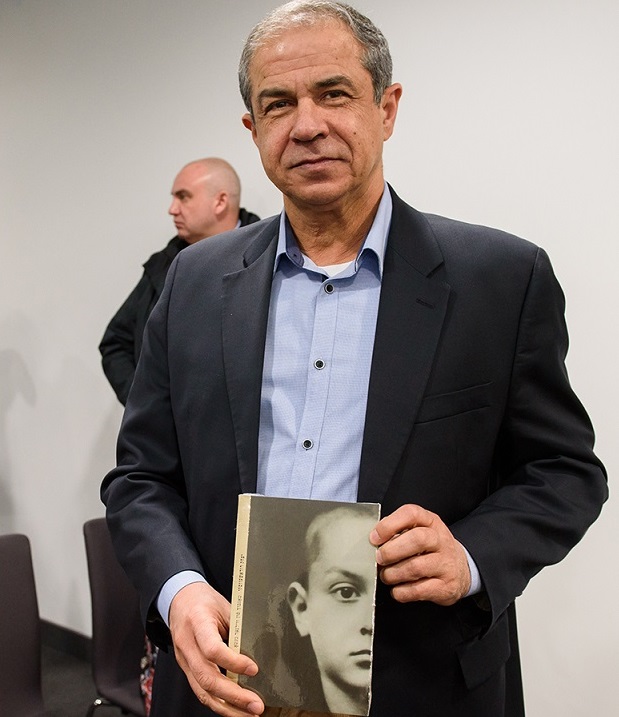

A large audience turned out for the book launch and Kvietkauskas, Vilnius ghetto inmate and Jewish partisan Fania Brancovskaja, Gregoravičiūtė, LJC chairwoman Faina Kukliansky and Israeli ambassador to Lithuania Amir Maimon spoke.

Rudashevski never abandoned his Jewishness in the face of suffering. “I am ashamed to be seen on the street, not because I’m a Jew, but because I am ashamed of my powerlessness. The yellow badges are sewn onto our clothing, but not into our minds. We are not ashamed of the patches! Those who put them on us should be ashamed,” Rudashevski wrote.

Kukliansky said the artist Sigutė Chlebinskaitė who designed the book had turned it into a work of art. Dr. Kvietkauskas noted the Rudashevski family house still stood at Pylimo street no. 52 in Vilnius. The boy’s father came from Molėtai and worked at a publishing house in Vilnius. His mother Rosa (also called Rokha) came from Bessarabia (Moldova) and his uncle Voloshin was an editor of the Vilner tog, the newspaper where Jung-Vilne debuted.

There were schools in the Vilnius ghetto, including upper classes where Rudashevski studied. In recalling their teacher he wrote how the children felt the loss of their teacher who had died in the ghetto and how they marched behind the funeral procession to the Jewish cemetery.

Vilnius ghetto prisoner Fania Brancovskaja called the book a gift and said at the launch her sister Rivka and Yitsele (i.e., Yitzhak Rudashevski) attended the same classes together. Reading the book again after many years, she said it was hard to believe what Yitzhak experienced. Brancovskaja escaped the ghetto just before the inmates were all murdered and became a forest partisan.

Yitzhak and his family were murdered at Ponar. His only living relative, Sora Voloshin, also a Jewish partisan soldier, discovered his diary after the war in the family’s hiding place and gave it to Abraham Sutzkever and Szmerke Kaczerginski. The book has been published in a number of languages previously–in English in 1973–but this is the first full edition in Lithuanian.