by Markas Petuchauskas

Now that some time has passed since the opening of the Samuel Bak museum, I would like to look back. To remember how this world-famous painter’s return to Lithuania began. To remember what I experienced. And these experiences date back to 1943.

Bak was probably never more open about himself than in the introduction to the Lithuanian translation of his book Painted in Words. He tells how Vilnius “tortured” him, how he sought to forget the city and was never able to do so. For more than half a century the artist placed a taboo on thoughts of Vilnius. On the city of his happy childhood and the land drenched in the blood of his family, where he would never set foot again.

I dare say one of the first unexpected reminders of Vilnius after sixty years was Pinkas. It is very nice that Bak was reminded of Pinkas in 1997 in the Lithuanian magazine Krantai (not speaking the language, the artist believed incorrectly this was a publication from the Lithuanian Ministry of Culture). The special third issue of the magazine, this was a publication by the Lithuanian Jewish Cultural Club which I founded in 1994. The magazine was set up at my initiative using club funds, and was intended to commemorate the Vilnius ghetto theater during International Art Days. Lithuanian National Museum employee Simona Likšienė wrote about the pinkas conserved at the museum in the magazine and included the title page.

The pinkas is a book of vital statistics kept by the khevra kadisha (in charge of Jewish burials and records of the dead). This pinkas was begun in 1880 and the last entry is from 1903. Sorting through and selecting documents and books for the Germans as forced labor, Abraham Sutzkever discovered the book and smuggled it into the ghetto. The great Jewish poet and his friend Shmerl Kaczerginski gave the pinkas to Bak and asked the young boy to fill the empty pages with his drawings. Thus was born the series of drawings by the small wunderkind. Two of the drawings appeared with Simona Likšienė’s piece in Krantai. The same issue of the magazine contained an excerpt from Sutzkever’s book “Fun Vilner geto” as well. This is probably the most remarkable portrait of Samuel Bak. Painted with Sutzkever’s quill, a prophecy foretelling the birth of a great Jewish artist. The story has shades of humor and excitement. “What is expressionism?” the boy asked the writer. Sutzkever admits the question has thrown him, and the boy doesn’t understand the explanation. “You know” the boy interrupted Sutzkever, “just draw it for me.” “I don’t know how, dear…” “How could you not know how to draw something you know?” the nine-year-old asked bringing up his shoulders in a shrug. “That evening I realized that along with all the other strange things of the Vilnius ghetto, another one had appeared.”

I return to 1943. My mother and I went to the opening of an art exhibition at the ghetto theater held in March. This was the first time I saw the young Bak. Here I, a twelve-year-old boy, also saw the first drawings by Bak, which I remembered my entire life.

Sixty years had to pass before I would again see Samuel Bak. In September of 2001 the artist and his wife Josée arrived for the opening of a large retrospective exhibition of his works at the Vilnius Picture Gallery of the Lithuanian Art Museum. We agreed to meet separately to talk more. Two “children” of the Vilnius ghetto theater sat in the foyer of Narutis Hotel. So the Creator ordered things, that both of our destinies led to the ghetto theater. Bak’s path led to art, while mine led to theater studies, but both paths began at the same Vilnius ghetto theater. Moved deeply, we went back in time to the distant past in our thoughts. I described to Bak my image of the 1943 opening of the exhibition by ghetto artists. Next to the poet and ideologue of the ghetto theater, Abraham Sutzkever, stands a short, thin boy in short trousers, on thin legs like matchsticks. Sixty years later that same boy, only now with long pants, slightly balding, slightly greying, tells the story of his life. And I tell mine. I remind Samuel of a drawing which really stuck with me. A boy with both hands painfully grabbing onto a branch, with head lowered, seeks with all his power his own way, as if he were trying to hide from the tragic and depressing destruction of his world. Even today, when I come across paintings by Bak, my eyes instinctively seek this drawing. It is like an exotic symbol of the fate of all the boys of my generation, of Sam, Alek Volkoviski-Tamir, whose world-class talent as a pianist shone on the ghetto stage, all the boys of that generation who survived and who were murdered.

When I attended the Bak exhibit, I was surprised the hall was almost emtpy, I didn’t see visitors. At the same time my acquaintances, art and cultural people, even artists, appeared not to have heard of the exhibit. Three months passed and the newspapers, radio and television remained silent, and there was only a half month left till the exhibit closed at the end of January. That’s when I got the idea to hold a discussion called “By the Canvases of Samuel Bak” to somehow get artistic Vilnius involved. Not coincidentally at the same time R. Mikšionienė in the newspaper Lietuvos rytas noted that if not for the Lithuanian Jewish Culture Club, cultural society would have missed the exhibition by the great artist.

I contacted museum director Romualdas Budrys first. We had been friends and worked together for several decades. Romualdas was surprised and a little thrown, and thought I should lead the event as its author. I wanted both of us to moderate the discussion. If only because Budrys had done so much work to make this essential exhibition happen. Its transport to Vilnius, moving the pictures–this was a gigantic and complex as well as expensive job, entailing much responsibility. Responsibility for setting up the exhibit and putting the canvasses on display also fell upon Vilnius Picture Gallery director Vytautas Balčiūnas and his fellow staff. The exhibit was set up in exemplary fashion. The priceless contribution made by these two men to promoting Litvak art is a separate topic in itself. I remember the impressive exhibitions of Rafael Chwoles and Mina Babenskienė, and ones such as “Artists of the Paris School from Belarus. From Belgazprombank, Museum and Private Collections” and “Lev Bakst: Era and Work” which Budrys and his wonderful collective held.

Budrys role was especially significant in bringing back the priceless legacy of artwork by Neemija Arbit Blatas, donated to Lithuania, and an exhibition of his paintings and sculpture in Vilnius which received international attention.

While I was preparing for the discussion at the museum among Bak’s pictures on exhibit, I asked the artist to write a letter to the audience. Dutiful and hard-working Bak immediately responded. I feel Bak’s letter to those who do art has not aged over the preceding 17 years.

Dear Friends,

I heartily welcome you to this reunion. My special thanks go to its organizers. Lauded be the fabulous invention of electronic mail that allows me, within the speed of a thought, send you these words.

It saddens me that I cannot speak to you now and answer your questions directly, but be assured, in my spirit I am with you. You are surrounded by my paintings, they are my best representatives and I hope that they will tell you what they are meant to say. I write now from my home near Boston. An immense chasm of time and of geography separates me from Vilnius. Yet the place feels very near. I close my eyes and transport myself easily to its ancient streets. The boy I was in my beloved hometown, and the man I am today, have a lot in common with each other. My painted as well as my written work reveal it.

Should you have any questions to ask, you may find most of their answers on the pages of my recently published memoir: „Painted in Words“. This book speaks of my family and myself, of our good, as well as bad and very painful times. It is also meant to bring my audience nearer to my paintings. I shall be even closer to you when in a future day this book sees light in Lithuanian.

When this day comes you`ll discover that my memoir is written in two voices. A voice of a man in his late sixties, the author who struggles with thoughts and ideas, and with the power of invading memories, in attempt to reach some understanding of a time bygone, and the voice of a child. A little boy who is discovering an absurd and cruel world, a world whose reality incessantly disintegrates into a myriad of shards.

I guess that my book must have been shaped by the way I paint. Most of my paintings speak in these two voices. Their exterior appears to be serious; it is painted in a manner that relates to a style of classical realism. But underneath its elaborate facade there is a bundle of interrogations and puzzles. Perplexed observations of a little boy, who tries to glue together the remains of a once destroyed and now perpetually crumbling reality. He is an outgrown child prodigy who through the craft of seemingly mature artist, tries to bring some repair to a world that hurts.

Through an extraordinary synchronicity in time, many of paintings exibited here shall soon travel to Germany, to my exibition in the Historical Museum of Landsberg am Lech. In May 2002 I shall go there in person. This Project echoes the voyage to Vilnius of my paintings, as well as my personal pilgrimage to this city of my childhood, although – as you may well image – the emotional implications of the two journeys do not compare.

Landsberg is a town located near the infamous death camp of Dachau. It is also known as the place, where an imprisoned Hitler wrote his „Mein Kamph“. My revisiting Landsberg is a return to a pleasant landscape of my early youth. It is the place where after my escape from the Soviets in Vilnius, at age eleven, I lived for three happy years in a camp for DPs. We were called displaced persons–homeless refugees.

Soon I shall be returning to Landsberg to be honored by its authorities with the award of the Herkomer Prize, the town`s major distinction for cultural merit. The closeness of the two exibitions, Vilnius and Landsberg, was not intentionally planned, their dates have happened to be a surprising coincidence. Many strange coincidences and magical moments have filled my life. Although their mystery cannot be elucidated, they provoke in me a search for a meaning.

Like in this case. I believe that exhibitions like the two I am speaking of do not happen in a void. They are the result of a definite design. And this intention together with a great investment of energies and means thrusts upon them a special need of presentation and understanding. Even if I toil to produce the best possible art, art for art`s sake, I know that its essence goes far beyond the purely aesthetic. It is not something I could ever hide.

The stuff of my paintings has much to do with my having survived the years of the war. So, let me explain.

Today, intolerance, hatred and terror openly menace us with destruction; screaming TV screens show our civilization in the combat for its survival. Civilization may survive and yet lose its soul in this battle, because other adversary forces, perhaps less visible, insidiously toil to obliterate the memory of mankind. Ignorance is dangerous, it is a time bomb.

Fortunately, a humanitarian effort opposes these malefic powers. Fortunately, there are individuals who know that art and culture are the best guarantors for the survival of our spirit. They know that if we wish to make this world a better place, we must become well informed, we must observe human behavior, study history, understand and accept the complexities of reality. My art happens to be the fortunate beneficiary of this humane intent.

The complexities of reality do not always provide us with a terrain of comfort. Undertakings that deal with the preservation of our souls can be quite painful. I wish to hail the courageous people who in the spirit of this struggle have found the force to deal with a shame that is imbedded in the history of their respective countries. Men and women who have come to terms with times in which entire generations of forebears were drenched in criminal waves of hatred and terror. I trust that their effort to avoid a repetition of past mistakes saves their moral stance and allows for the healing of old wounds. And I must admit, although it may sound somewhat pretentious, that I am greatly touched when my paintings are given the occasion to serve this noble purpose of reparation.

My biography, as you all know, began in 1933 in this magical city of Vilnius, then the crown of Yiddish culture, the Jerusalem of Lithuania. That Vilnius was murderously destroyed in WWII. My visual and verbal works carry in them, with the shards of this experience, a specific testimony. And when they connect with today`s audience their message sheds a revealing light on the often-overshadowed stages of our tragedy.

Since education is the key to change and growth, the exposure of my art to a larger public transcends the ego of my artistic person. My paintings, and now my memoir, should be considered as transportable memorials af a wandering Jew that tries to affirm the remembrance of a loss, which is beyond repair. Art-historical, aesthetic or stylistic considerations deserve much respect; these fascinating and much debated fields must be left to their qualified specialists.

The discourse that I propose to the audience of my contemporaries is the discourse of facing history and ourselves. Of looking at our past with the conscious awareness that the dangers of oblivion, revisionism and the obliteration of a shameful past threaten the very structure of our society. That it is necessary, more than ever before, to preserve our free world from the illusion that all battles have been won. It is a matter of saving the soul of our civilization.

Samuel Bak

January, 2002

The Lithuanian Art Museum space was filled with people who listened to this letter read out loud. Budrys and I sat together at this fancy table from I don’t know what century. I invited Art Academy dean professor Arvydas Šaltenis to come. He in turn brought many of his colleagues, young artists and our “living classics.” I asked the heads of the Union of Artists to invite their members. I invited artists in different fields and cultural workers. Many students also attended. We invited press, radio and television journalists.

I invited my old friend as well who conducted club events involving art, Alfonsas Andriuškevičius, a critic and poet and winner of the National Prize. Andriuškevičius said he found something exception in Bak’s work in the 20th century Lithuanian art context, a “flood of symbols and allegories.” “It’s obvious the artist’s subconscious has a tendency towards surrealism, while his consciousness very actively directs his work towards neo-classicism and neo-realism.” Art history expert Aleksandra Aleksandravičiūtė noted “paraphrases of different periods of art history” characteristic in the artist’s work, which becomes “a reconstruction of that other, lost world.” Although Bak’s artistic roots were in the Vilnius ghetto, artist Arvydas Šaltenis said his later work was affected by global art processes. The professor, who has always given great attention to Litvak art, noted Bak’s spiritual connection with Vilnius and mentioned the talented young painter Solomon Teitelbaum, whose canvasses, although utilizing different expressive techniques, exude a markedly Jewish mentality.

In the wide-ranging discussion which grew up around the subject, the thoughts of the artists Gediminas Jokūbonis, Mina Babenskienė and Aloyzas Stasiulevičius stood out. Jokūbonis, who had been interested in Litvak art for many years and attended the programs I held, expressed enchantment with Bak’s search for and discovery of artistic expression. Jokūbonis said Bak had open up for him a new and unique understanding of the world.

Aloyzas Stasiulevičius noted the many Jewish artists from Lithuania, including Isaac Levitan, Chaim Soutine, Neemija Arbit Blatas, Moshe Rozental, Samuel Bak, Markas Antokolskis, Jacque Lipchitz… All of them for a time studied here and left here for distant lands. Now their work is gradually returning. Stasiulevičius felt Bak had painted like a master items, drapery and human figures, but there was always a painful past included, traces of ruins, a hidden barb. “In many places we recognize the rhythms of the walls and brickwork of Vilnius. In almost every work there are wilted flowers, broken dishes, shot and damaged fruit and a mournful sky shining in the upper part of the paintings.”

I sent a long “report” on the event at the Art Museum to Weston [Massachusetts, where Bak is resident], noting Bak had suddenly become famous in Lithuania following the discussion. The major newspapers and radio and television channels told the story of the artist’s life and work. Some in more detail, some more briefly. The Atgimimas newspaper even published Bak’s letter to exhibition visitors translated by my wife. Later I sent newspaper clippings with comments in English to Weston by post. Bak it seems was so deeply impressed that he called my “By the Canvases of Samuel Bak” discussion that in his memoirs he called it “a symposium that local academics dedicated to my art.” And who am I contradict the artist’s words?

I invited a special guest, Rimantas Stankevičius, to the “By the Canvases of Samuel Bak” as well, a person who has done a great deal to make a home for Bak’s paintings in Vilnius. The long-standing foreign affairs “minister” of the Lithuanian parliament whose small car stood outside Bak’s home in Weston in the autumn of 2000. Stankevičius has been studying the Holocaust in Lithuania for many years, collecting material and writing about rescuers of Jews, and is concerned with keeping their memory alive. (Incidentally our mutual interest in commemorating the rescuers is what led to our friendship of many years). Rimantas came to Bak’s home as he sought to commemorate those who rescued Bak and his mother. If my club publication Pinkas brought Bak back to Vilnius in his thoughts, Rimantas was the first to invite him back. That was when the word “exhibit” first came up. As Bak recalls, on that day “the gap between Lithuania and Weston, between the darkness of those times and the sunny reality of today, started to close.” Back in Vilnius Stankevičius began casting around for holding an exhibition of the artist’s works, meeting with a number of people and approaching member of parliament Emanuelis Zingeris for support. He jokingly called those meetings “gatherings of the Bak club.” In the excitement of the opening of the 2001 exhibition at the Art Museum, there was no lack of high-sounding reassurances and promises by functionaries to the effect that very soon a book of Bak’s memoirs would be published in the Lithuanian language. But “Painted in Words” only appeared in 2009, in largest part due to Stankevičius’s efforts. I can witness to this because I attended and spoke at the impressive book launch Rimantas held at a gallery. It’s very symbolic that this was next to the former archive on Šv. Ignoto street, where Bak and his mother hid. Rimantas really became, as Bak put it, “a priceless friend and guardian angel,” his Ambassador in Lithuania. The dinner Stankevičius held for Bak and his wife over the course of time became a tradition of our three families, a regular evening party. It expanded to include our home. The tradition gained new momentum later when Samuel brought now one, now another of his grandchildren to Lithuania. Sometimes they were accompanied by their mothers, Bak’s attractive daughters. This was a unique bar mitzvah present for one of the boys. Bak taught his grandchildren about the family’s Lithuanian roots and the unfading beauty of Old Vilnius. This is how my wife and I had occasion to get acquainted with Bak’s descendants.

Stankevičius threw the biggest dinner party, which was attended by the entire “crew” of Samuel’s friends from abroad, when the Bak museum opened in Vilnius. It wasn’t just the biggest, it was the warmest. The most sincere. Not just toasts but interesting memories, happy and sad, were shared. It was very pleasant to meet and speak with the playful and witty Bernhard Pucker who arrived with his wife Sue, who are the owners of a gallery in Boston where the majority of Bak’s works are held.

I hope the “triumvirate” of our three families brought together by the person and talent of Bak will stand the tests of time and will brings us back together again for many a dinner party.

Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum director Markas Zingeris played an important role in bringing Samuel Bak to Lithuania in the fall of 2017. It wasn’t easy to build the Samuel Bak museum. Nonetheless, we have become witnesses to a wonderful exhibition created by the talented collective of professionals and enthusiasts at the museum.

The Vilnius municipality also received the artist in a beautiful way. Mayor Remigijus Šimašius ceremoniously presented Bak the regalia of honorable citizen of his hometown at the Old Town Hall.

I’d like to return to April in 2002 when Bak and his wife attended International Art Days at my invitation, an event dedicated to the 60th anniversary of the ghetto theater. Thus another step in the direction of Vilnius was taken.

If during the first Art Days (1997) I attempted to remove the veil of oblivion from the Vilnius ghetto theater and place it on the Lithuanian cultural map, in 2002 I focused on notable artists of the Jerusalem of Lithuania who celebrated it with heroic efforts. Most of the people who established the theater were artists who constituted the artistic elite of the Jerusalem of the North. This was a large group of cultural people who were united in spiritual resistance. They included many famous writers, directors, actors, musicians and artists. Marking the 60th anniversary of the tragedy of the Shoah in Lithuania, we wanted to honor the memory of hundred of talented European artists who perished in the flames of the Holocaust.

During the Art Days, on April 22, we unveiled a memorial plaque, at my initiative and financed by funds the club raised, on the outside wall of the former theater (Oginski Palace) with an inscription in Lithuanian and Yiddish, reading: “By virtue of the heroic efforts of the artists of the Jerusalem of Lithuania, in this place the Vilnius Ghetto Theater persisted in its activities in the years 1942-1943.” In preparing the commemorative plaque and inscription, I wanted to emphasize especially that the Vilnius ghetto theater was the child of many Jewish artists and of all of the Jerusalem of the North. And those who flocked to the theater supported it with their spirit, energy and stoicism.

Members of the Government and parliament attended the ceremony. The speaker of parliament spoke, stressing the importance of the ghetto theater to Lithuanian culture and the spiritual resistance of its founders. I take joy in the fact I unveiled this plaque with Samuel Bak and Aleksandr Tamir participating.

I remember the words of Alek Tamir he spoke during the final concert of Art Days at the National Philharmonic: “I would like to come back again and to perform with Sondeckis’s orchestra.” A man who by his own admission had avoided Lithuania for sixty years, which had remained in the child’s mind as the land of the nightmare of mass murder, and who had never planned to return here. Another child of the ghetto had a similar idea, Samuel Bak. His “return” which began with the large retrospective at the Vilnius Picture Gallery in 2001 continued through the Art Days at the former ghetto theater. Bak and Tamir after sixty years again both got back up on the same theater stage they knew so well. They were both moved as they shared their experiences. Tamir spoke about the death of his family, about his father the famous Vilnius doctor, and about his own miraculous rescue. Bak recalled his debut in the theater foyer and his rescuers, and spoke about the international significance of the commemoration of the ghetto theater. He remembered the head of the ghetto theater, the director Israel Segal, whose productions for the Jewish stage he saw at the displaced persons camp in Landsberg. Bak later spoke with the Litvak Segal in Israel. At Segal’s request the seventeen-year-old Bak did his first stage design for three one-act plays presented at the Yiddish Theater in Israel. Israel Segal dedicated his entire life to the Yiddish Theater. He asked the artist to make the stage decorations “cost little, be weightless, fold up easily and fit into a very small truck that would transport it all over the country.” At that time the Yiddish-language theater was having a hard time of it in Israel where Hebrew was king.

Bak and Tamir were very dear people to me. I called them “children” of the ghetto theater. And I was also a “child” of that theater, although, of course, I can’t compare myself with these artists of great talent. My career in theater studies began in this theater hall. For Bak and Tamir, this same theater hall opened the way to High Art.

Samuel also bowed to his rescuers, the priest Juozas Stakauskas, the teacher Vladas Žemaitis and the Polish nun Maria Mikulska. A plaque commemorating these Righteous Gentiles was unveiled on the outer wall of what was the archive during the war at Šv. Ignoto street no. 5. This is where they hid the young artist and his mother.

It is said that if you save a person, you save an entire world. But isn’t the restoration of a person’s connection with his homeland also a rescue? Of that same world which for millennia was blown up by all-consuming ethnic and religious hatred. Hundreds of known and unknown heroes opposed that hatred with their lives and those of their families. Such that humanity thirsts for peace and concord, whose huge cost is not measurable by any measurement. And the world of the Righteous Gentiles it turns out isn’t so weak after all, able to place this on the scales of the conscience of humanity.

That Lithuania is slowly changing is being understood even by those who for many years have turned their backs on our country, and although that is a very sad thing, they had a serious basis for doing it.

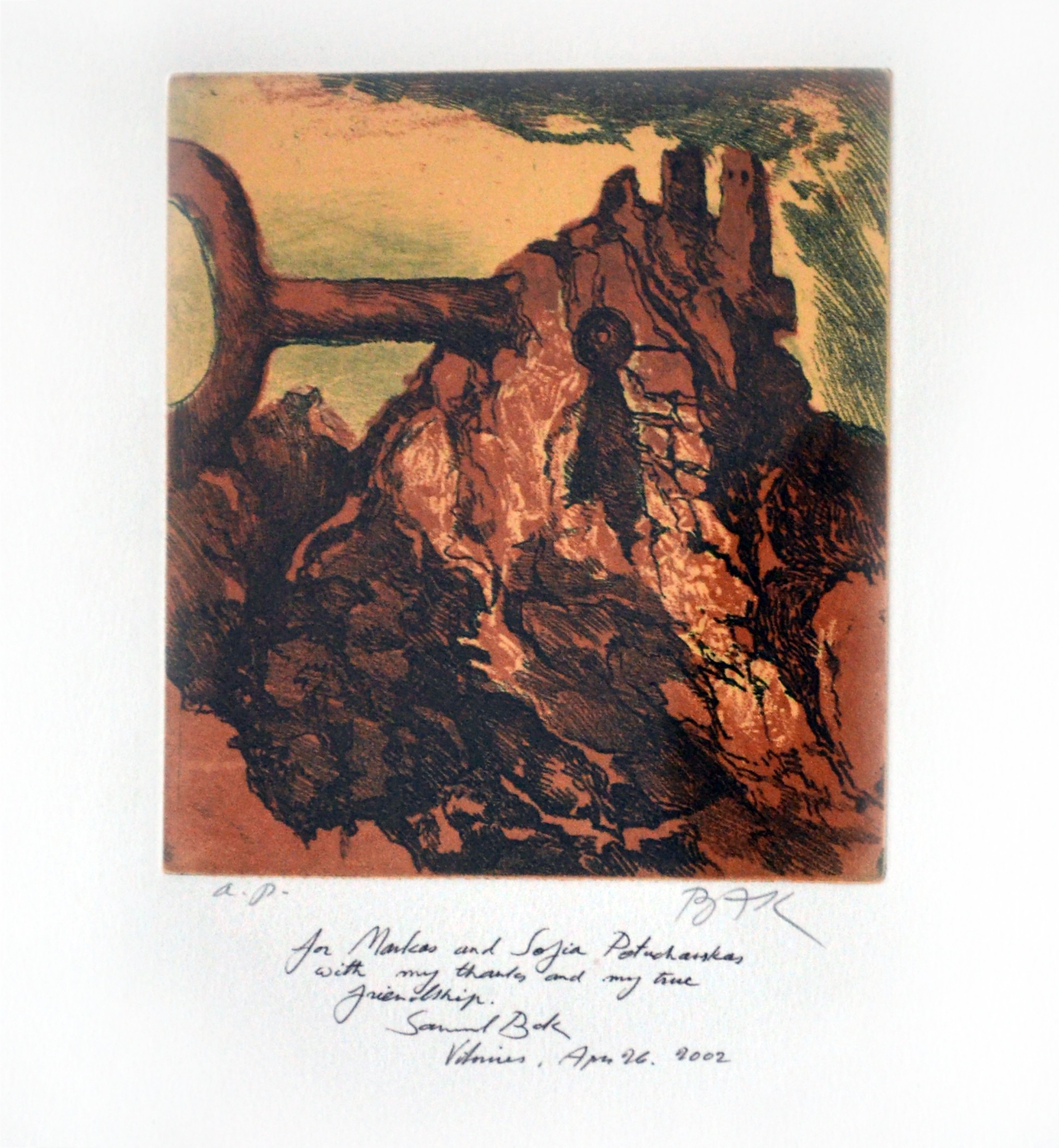

Just before he flew back to the United States Samuel gave me a painting with a warm dedication. This painting by Bak is very dear to me. It is an unfading witness to our friendship. It is also a high assessment of International Art Days.

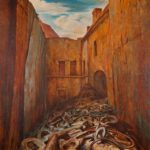

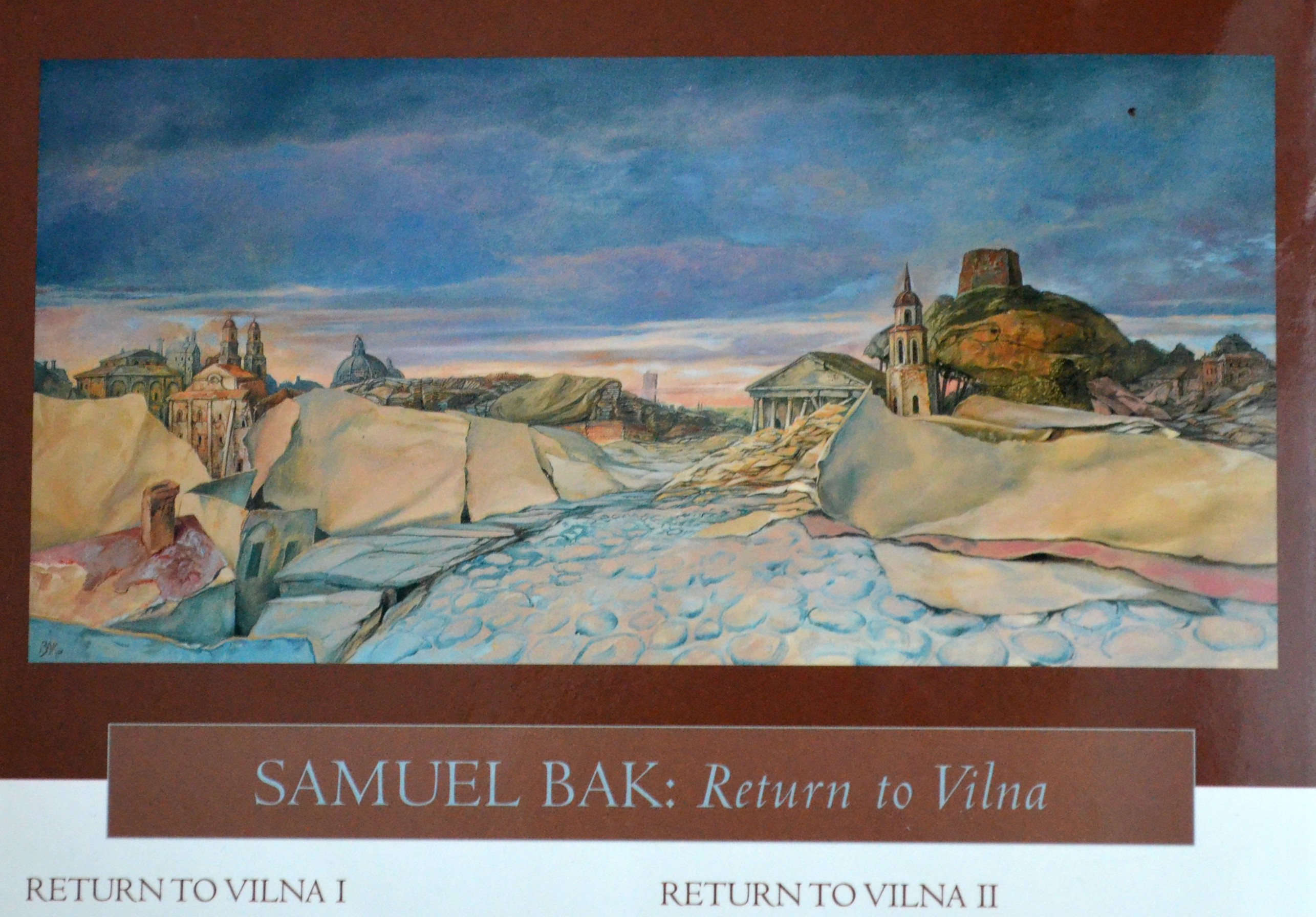

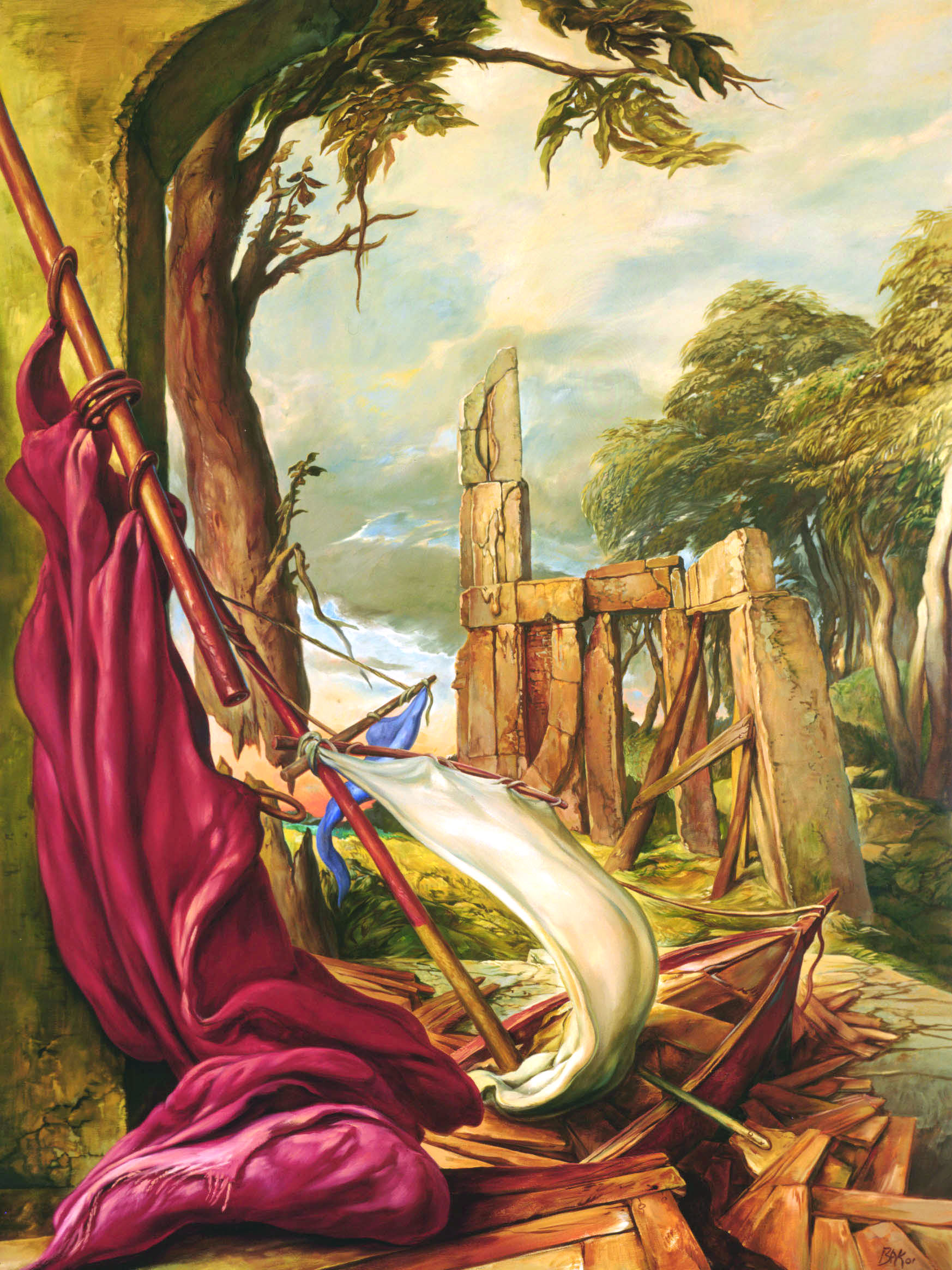

The greatest assessment of the commemoration of the ghetto theater, however, is, in my view, the huge creative stimulus which the artist experienced upon returning to Weston after Art Days. Thoughts of Vilnius continued to “torture” him without stop, kindling a bonfire of new artistic visions. As Bak put it, even before drinking his morning coffee, he ran directly to his studio to paint: “My studio reverberated with Vilna.” He painted at a lightning pace with such an energy that he soon had a whole collection of paintings. The new exhibit was called that, “Return to Vilna.” The exhibit was held by the Pucker Gallery in Boston. When I received the exhibit catalogue, dedicated to me, even the reproductions struck me with their newness. This was the Bak I knew, and at the same time, a different Bak, reborn. The canvasses in “Return to Vilna” truly shed a new light on the Vilnius ghetto and its theater. I saw broken stone statues recalling the eternal flame. Cut wooden chimneys flying through the air, as if they were trying to cover up Ponar, that horrid and nonetheless visible space of degradation and massacre. I saw desecrated, ruined Torah scrolls bound as towers of documents, looking like the destroyed synagogues. All of this, Bak writes, “tells of the destroyed culture, of the Jerusalem which disappeared in the flames.”

Bak told me much about the writer Abraham Sutzkever, with whom he also had a friendship after leaving Lithuania. When I began preparing an evening to celebrate Abaraham Sutzkever’s ninetieth birthday, I asked Samuel to write down some of his memories about this Yiddish poetic genius. I quote from his letter:

“Sutzkever is one of the greatest Yiddish poets. A prominent member of Jung-Vilne, already world-famous before the war, he was an influential force in the cultural life of the ghetto. He treated me, in spite of my nine years of age, as if I were his closest friend. He spoke to me about his friendship with Chagall or Mane Katz. He would show me again and again and try to explain the reproductions in a couple of art books that he kept under the bed of his room in the ghetto. Together with the poet Kaczerginski he put in my hands the ancient Pinkas. My job was to fill it with sketches and drawings.

“Throughout the years I have kept an ongoing friendship with Sutzkever. We met many times in Tel Aviv, New York and Paris and had long talks. Age has limited his mobility and our meetings in recent years have not been very frequent. Recently he dedicated to me a book of his own prose. The last chapter of that volume is a lengthy essay about the child-artist I was in the ghetto, about our conversations of that time, about the painter I have become. It is for me one of the most rewarding and poetic texts I know of concerning my art.

“Sutzkever has always given me extraordinary support. It was he, along with Kaczerginski, who chose the watercolors and drawings that were to be shown in the ghetto exibition. The preparations for the show were not as simple as one might imagine. Several established artists among the ghetto`s surviving inhabitants had been angry with the jury for admitting me to the show. Furious about „sensationalism“ as they called my participation, and even more about the large space allocated to my work, they got hold of my drawings and pasted them up edge to edge against each other, making of them one big patchwork.

“Szmerke and Avrom, my two devoted poet-patrons, discovered the scheme and were enraged. They toiled a whole night with the help of another two friends to undo the work of my ‘aggressive competitors.’ The carefully separated drawings were re-pasted on independent sheets of Bristol paper and shown that way.

“My patrons decided I should never learn about this mean behavior. I was too young to lose my innocent belief in the human heart. One silly outbreak of jealousy should not undermine my trust in friendly and collegial relations between artists. But the petty intrigues and bad feelings that collective art affairs seem doomed to generate, even in times as tragic as these, quickly brought the whole matter to light. Samek Bak, the child-painter, had to add this unpleasant event to an inevitable list of disenchanting ‘learning experiences.’ They are part of every artistic career.”

Samuel Bak always participated “in absentia” in my club’s events, especially those dedicated to Litvak artists. His thoughts sent across the Atlantic by internet were part and parcel of the discussions held by the club. For instance, regarding the work of Ben Shahn, born in Kaunas, he wrote me:

“I am glad that you dedicate an evening to Ben Shahn. It is a very special moment of emotion to speak about one of the heroes of my artistic youth, the painter Ben Shahn.

“I must have been eighteen, when I first discovered in Tel Aviv a book of reproductions of Ben Shahn`s paintings, and they captivated me. Here was an artist who reached very high standards of formal qualities, but did not believe that they were an end in themselves. At the core of his creation was a great concern for human destiny, a deep devotion to the ideals of social justice, and a virbant love for the roots of his Jewishness. In some way, he was one of the marking stones that have directed me to my artistic choises.

“In somber days like these, when anguish, disenchantment, cynicism and ruthless climbing on the ladders of success, typifies much of the atmosphere in which we live and act, the genius of this great artists shines with a very special light.”

Samuel Bak’s connection with his homeland, painfully broken off a half century ago, is being restored now, with difficulty. First in thought, later in a restoration of creative dialogue.

I feel that the last supper will not be the last. I feel Bak and his dialogue of creation with his homeland has no ending point. My optimism is supported firmly by the artist himself in his book “Painted in Words” where he states one of his certainties about his ethnic identity: Ikh bin a vilner.

Prof.habil.Dr. Markas Petuchauskas

January 8, 2018

Vilnius

§§§

At the request of professor Markas Petuchauskas, the Pucker Gallery has sent digital reproductions of these paintings and has kindly allowed them to be published on the Lithuanian Jewish Community webpage. The Pucker Gallery houses many of Bak’s works.

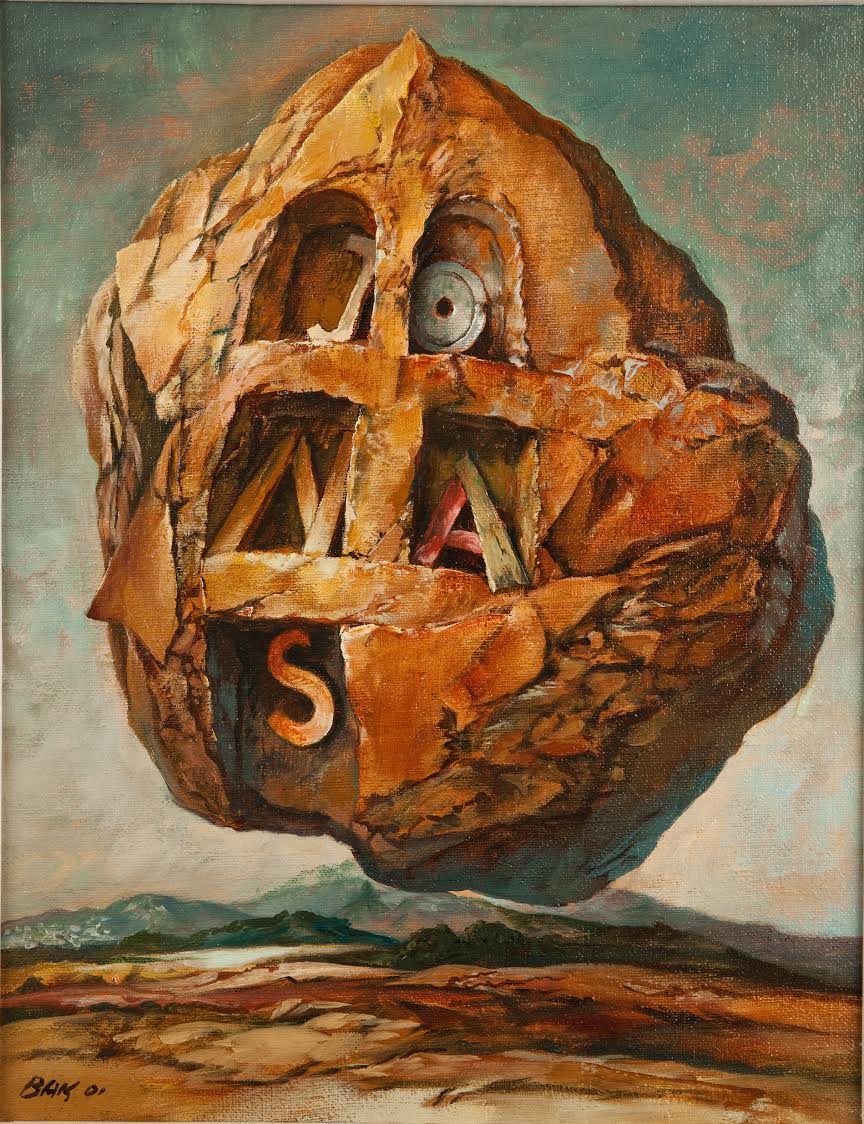

“I selected the photographs of pictures from the artist’s catalogue ‘Return to Vilna.’ These two collections of paintings have not been shown in Lithuania. They were selected for the article ‘The Return of Samuel Bak’ and illustrate my statements about the rebirth and new creative ferment of this impressive painter,” professor Petuchauskas wrote.

“It’s also appropriate here to show the painting Bak dedicated to me so movingly when he was enchanted by the International Art Days commemoration of the Vilnius ghetto theater in 2002,” he said.

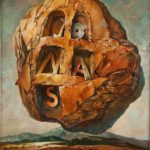

Yona IV

“I would like to single those paintings, especially painful ones memorializing the artist’s losses, such as that of his father, Yona, his grandmother, Shifra’s Memento and his other grandmother, Rachel’s Memento,” professor Petuchauskas wrote in a letter to the Lithuanian Jewish Community.

Shifra’s Memento

Rachel’s Memento