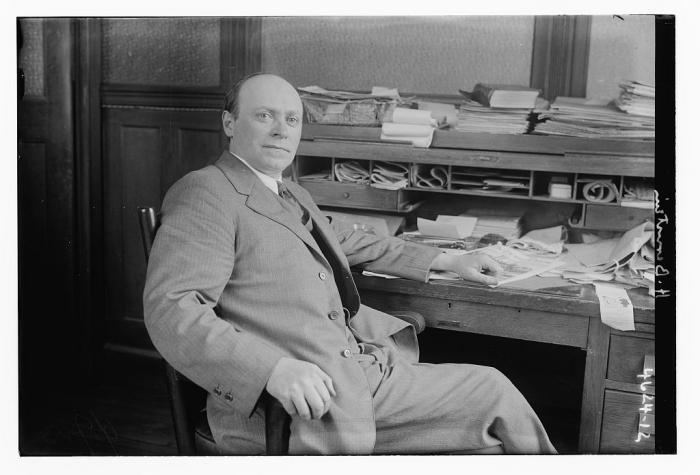

While there are many Litvaks in the world who are known for great accomplishments and high intellect, a recent book in Lithuanian called “Pasaulio lietuviai: šlovė ir geda” (Alma littera, Vilnius 2016) [Lithuanians of the World: Glory and Shame] features a perhaps lesser known Litvak figure whose accomplishments were no less important, Hermann Bernstein.

Hermann Bernstein was born either September 20 or September 21, 1876, on what astrologists would call the cusp of Virgo and Libra. His exact birthplace is also a bit “on the cusp” as well: he was born in or near what is now Kudirkos Naumiestis, Lithuania, so named in 1934 after the Lithuanian patriot Kudirka, formerly known variously as Władysławów, Naumiestis (and German and Polish versions of “New Town”) and Naishtot and Naishtot-Shok or Naishtot-Shaki in Yiddish. But here’s the cusp: the respected Jewish Encyclopedia says he was born in Schirwindt, the now-gone East Prussian town just across the bridge over the Šešupė river from Kudirkos Naumiestis. Both towns apparently comprised a sort of unity with the East Prussia-Russian Empire border running through the middle. Whichever side of the bridge Hermann was born on, the early Zionist activist Rabbi Abba Hillel Silver was born nearby in 1893, which is the same year Hermann and his family arrived in America after moving for a time to Mogilev in what is now Belarus, where Hermann attended a free Jewish school.

The move to Chicago wasn’t as fortunate for the family as it might have been. Hermann’s father David, a Talmudic scholar, came down with tuberculosis almost immediately upon arrival, and the children all went to work in factories. Hermann’s propensity for writing refused to be ignored, however, and he began doing journalism as early as 1900. He contributed, among others, to the New York Evening Post, The Nation, The Independent, and Ainslee’s Magazine. He was the founder and editor of Der Tog and an editor of the Jewish Tribune and the Jewish Daily Bulletin. As correspondent for the New York Times he traveled to Europe often. In 1915 he went to Europe to document the situation of Jews in the war zones.

According to Victoria Woeste:

“Bernstein, a novelist and poet of some repute, won acclaim for his accomplishments in investigative journalism in the 1910s. He was driven ‘to lay bare the operations of Russian totalitarianism, whether Czarist or Bolshevist, especially in so far as it affected the fate of Russian Jews.’ His reporting revealed ‘the involvement of the Russian secret police in the case of Mendel Beilis, the Jew wrongfully accused of the ritual murder of a gentile boy’ in 1911, and he also documented social and political conditions in Russia before and after the Communist Revolution.”

Bernstein later translated Beilis’s “Story of My Sufferings.” In the 1920s Bernstein wrote for the New York American and the Brooklyn Eagle, reporting from Europe and writing frequently about Russia.

In 1918 Bernstein revealed secret correspondence between tsar Nicholas II and kaiser Wilhelm II and published it in a book called “The Willy-Nicky Correspondence,” published by Knopf with a foreword by Theodore Roosevelt. Bernstein summarized the contents as follows:

“During my recent stay in Russia I learned that shortly after the Tsar had been deposed, a series of intimate, secret telegrams were discovered in the secret archives of Nicholas Romanoff at Tsarskoye Selo… The complete correspondence, consisting of 65 telegrams exchanged between the Emperors during the years 1904, 1905, 1906 and 1907, forms an amazing picture of international diplomacy of duplicity and violence, painted by the men responsible for the greatest war in the world’s history. The documents, not intended for the eyes of even the Secretaries of State of the two Emperors, constitute the most remarkable indictment of the system of governments headed by these imperial correspondents.”

He wrote: “the Kaiser is exposed as a master intriguer and Mephistophelian plotter for German domination of the world. The former Tsar is revealed as a capricious weakling, a characterless, colourless nonentity.” They “both talked for peace and plotted against it.”

In 1915 Bernstein published a book called “La Rekta Gibulo” in Esperanto, a translation of “The Straight Hunchback,” a story in Bernstein’s “In the Gates of Israel.”

In the early 1910s Bernstein advocated liberal immigration policies and was a member of the Democratic National Committee, working to elect Woodrow Wilson in 1912.

Bernstein met Herbert Hoover at the Paris Peace Conference and supported his bid for the presidency in 1928. Soon thereafter, Bernstein published “Herbert Hoover: The Man Who Brought America to The World.” In 1930 Hoover appointed Bernstein United States ambassador to Albania, which he held until 1933. He helped forge several treaties between the US and Albania and received an award from King Zog for his service to Albania, the Grand Cordon of the Order of Skanderbeg.

Bernstein’s most prominent claim to a place in the history books came in 1921 when he took US industrial giant Henry Ford to task for the latter’s very public anti-Semitism. Responding to Henry Ford’s printing of 500,000 copies of the notorious anti-Semitic forgery “Protocols of the Elders of Zion” as well as a series of anti-Semitic articles under the title “The International Jew” in Ford’s newspaper Dearborn Independent, Bernstein published the book “History of a Lie,” a book about the Elders of Zion hoax.

Bernstein sued Henry Ford for libel as well. In the August 20, 1921, issue of the Independent, Bernstein was named the source who revealed to Ford the supposed worldwide Jewish conspiracy. “He told me most of the things that I have printed,” Ford claimed in the article, which labeled Bernstein “the messenger boy of international Jewry.” Bernstein denied the allegations and sued Ford for $200,000 in 1923. He told the press that he was performing a public service by allowing the American people to get a “true picture” of Ford’s “diseased imagination.”

Bernstein was represented by Samuel Untermyer. The suit languished because Bernstein and his representatives were never able to serve Ford with a subpoena. Ford had many allies among the political and law enforcement officials of Michigan and elsewhere as well as a large private security force. Bernstein and Untermeyer did, however, succeed in getting New York state officials to agree to impound all copies of the Independent that entered the state.

Due to Bernstein’s suit and others by Louis Marshall and Aaron Sapiro, Henry Ford eventually issued a half-heart “Apology to Jews.” By 1935 the Nazi Party in Germany was requiring all German schoolchildren to read the Protocols and Bernstein published a more comprehensive exposé of the anti-Semitic hoax called “The Truth About the ‘Protocols of Zion’: A Complete Exposure.” Bernstein died that same year, while Henry Ford was awarded the highest state award for foreigners created by Adolf Hitler himself, the Grand Cross of the Supreme Order of the German Eagle on his 75th birthday, presented by the German ambassador himself in 1938. Ford’s anti-Semitic book “The Eternal Jew” was translated into German, inspired many Germans to anti-Semitism and was even cited by a Hitler Youth at the Nuremberg trials as the ideological source of his belief in Nazi doctrines of hate.

Henry Ford continued, according to rumor, to send presents to Hitler on Hitler’s birthday throughout the war, Ford European subsidiaries exploited Nazi slave labor and Ford also continued to “Americanize” his mainly immigrant work-force back home with classes in English and other “improvement” programs, the goal of which was to create a “new American” without Old World baggage, exactly the sort of “rootless cosmopolitan” Ford and fellow Nazis said lay at the root of “the Jewish problem.”

While Ford might appear to have won by the superficial measures of history, it’s clear Bernstein’s accomplishments were more enduring, albeit esoteric. Of course it would have been a much greater thing for humanity if Bernstein had changed Ford’s mind instead, but such things weren’t as likely to happen back then, when, as McLuhan put, vertical instead of horizontal communications systems were the rule. As Robert Mulcahy put it in his article “Henry Ford and His Anti-Semitism”:

“This belief in his own righteousness led Ford to take on a more sermon-like tone with people in telling them how to live. Ford surrounded himself with a very small, tight circle of advisors. Access to this inner circle was strictly controlled by Ford’s long-time personal secretary, Ernest G. Liebold, who would protect his ‘Boss’ for many years to come. This type of management style may have been conducive for getting things done, but it also alienated Ford from what his workers were thinking and created an isolationism that proved hard to bridge. This sense of ‘being out of touch’ partially explains Ford’s later actions.”

Perhaps it’s too much to expect the minds of the powerful, outside of some exceptional and neutral place such as Switzerland, might hear the soft but insistent voice of the leaker, of the truth-teller, but if you live long enough, you’re bound to see everything, even a king able to read the writing on the wall.