The Lithuanian Jewish Community hosted the launch of “Laikas and kitas,” a Lithuanian translation of Litvak philosopher Emmanuel Levinas’s book “Time and the Other,” on January 25. Translator Viktoras Bachmetjevas, an advisor to the Lithuanian minister of culture, was there, as were Dr. Aušra Pažėraitė of the Religious Studies Center of Vilnius University, philosopher Dr. Danutė Bacevičiūtė of the same center and Vytautas Magnus University Public Communications Cathedral teacher Algirdas Davidavičius. The four held a panel talk and talked about the book based on a series of lectures by Levinas.

The Jonas ir Jokūbas publishing house published the book with support from the Goodwill Foundation.

Dr. Aušra Pažėraitė agreed to talk more about the Litvak philosopher for www.lzb.lt.

§§§

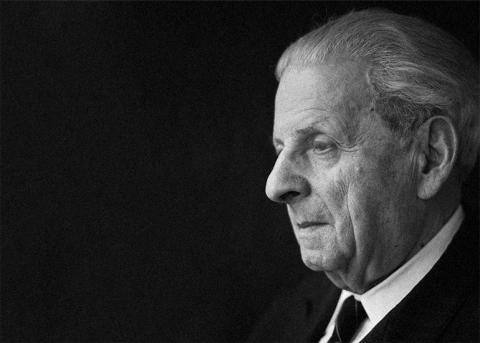

We can speak of two aspects of the connection between one of the most prominent philosophers of the 20th century, Emmanuel Levinas (1906-1995), and Lithuania. First, it is known he was born and grew up in Kaunas and his parents were also from Lithuania. He was born in Kaunas January 12, 1906, old style, which is December 30, 1905, on the Julian calendar, or the 15th of Tevet on the Hebrew calendar. Kaunas then was the seat of the Kovna guberniya in the Russian Empire. According to the entry in the vital records of the Kaunas Jewish community, his father was Kaunas resident Yekhiel Levin and his mother was named Dvoira. There’s also a date for his circumcision in the entry, January 6 according to the Julian calendar.

His father was also a native resident of Kaunas, born there to Abraham Levin and Feige in 1878, and his mother came from Ylakai, where she was born in 1881 to Moshe Yitzak and Eta Gurvich. He attended a Jewish primary school in Kaunas until World War I. The family was forced to evacuate as many Lithuanian Jews were during World War I. The Levin family ended up in Ukraine, where Emmanuel was accepted at a gymnasium in Kharkov, where at the same time a Kaunas boys gymnasium had been relocated. The story goes the entire family was overjoyed because this represented an opportunity for Emmanuel to pursue a higher education somewhere in the Russian Empire, but the war ended and the chaos and changes of the revolution began and Lithuania achieved independence, the family returned to Lithuania.

Here they received Lithuanian citizenship and Emmanuel Levinas entered a private Jewish gymnasium in Kaunas in order to finish high school before entering university. He attended the gymnasium for three years. The three upper grades he attended were still being taught in Russian, but there were also intensive Hebrew classes. Lithuanian language classes were introduced and he learned Lithuanian. He wrote one of his very first philosophy texts in Lithuanian. The curriculum included some basic instruction in Judaism and the Jewish holidays were celebrated, but it seems there was nothing of what today is called Lithuanian Judaism, only, as he later put it, “bloodless” generalities without the classic texts of rabbinical literature.

What is this “Lithuanian Judaism” and what was Levinas’s intellectual and religious connection with it? I would like to quote from the book “Lire Lévinas” by Solomon Malka. He says for many years he attended Levinas’s Saturday Torah study activities during which they read and analyzed Talmudic texts. He writes:

“Emmanuel Levinas’s Judaism had put down roots in his native Lithuania (one day Gershom Scholem would say, with a sardonic smile: ‘He was more of a Litvak than he even knew.’). Born in Tsarist Lithuania, early on he acquired a double formation: the classical, fed on Russian literature, and the Hebraic, since he had a Hebrew language and Bible teacher. He would often say he never felt any contradiction or internal division in this double culture. Hebrew culture for him was always a universal culture.

“Lithuanian Jews, it seems, in a certain way experienced secularization in the heart of Judaism. In any event, this land remained in Jewish literature as the symbol of a proud bastion which opposed to the very end the attacks of the Hassidic movement of Central and Eastern Europe in the 18th century. The domain of the mitnagdut.

“Lithuanian Judaism, this is a tendency towards sobriety. Not against emotion, but opposed to a certain drunkenness of the spirit at the popular level. … The Vilna Gaon himself was a great cabbalist. But he always believed the Zohar complements the Talmud. And I, for my part, continue to think that the Talmud gives measure to the true Jewish spirit, even that of the Kabala.” [from a conversation with Levinas published in the November, 1981, issue of L’Arche.]

This is a tradition seeking to integrate Hassidism into classicism, and also to encompass its own emotional overflows. This is a culture of sobriety and of a certain kind of wisdom, the Mussar, the literature of moral growth, illustrated by, among others, Rabbi Israel Salanter, who revealed the sum of its worth. Levinas harbored a kind of special fondness for the deeds of this rabbi, one of whose phrases which corresponded to his own thinking he often repeated: “The physical needs of my neighbor are my spiritual needs.”

These words serve to answer the questions posed: despite the fact Levinas didn’t identify himself with Lithuanian Judaism, the heritage of Lithuanian rabbinical thought was dear to him. Even though he discovered the significance and meaning of the classical rabbinical texts, and especially of Talmud study, outside Lithuania, not at Lithuanian yeshivot, but when he was already living in France, studying privately with a wandering Jew named Shushani. The latter was, by the way, the teacher of Elie Wiesel, who called him “the eternal Jew.” Solomon Malka thus described Levinas’s meeting with him:

“It was said that he came from Lithuania, received form in the yeshivas, spoke Yiddish, had gone through the old yishuv of Jerusalem [the Ashkenazi Jewish community which settled in the land of Israel before the great aliyah of the 19th and 20th centuries]. He lived for a long time in Morocco. It was said he drank. Well, at least he didn’t have a permanent place of residence and knew nothing of a trade. A bachelor who lived from Talmud lessons which he handed out in full portions. Occasionally he disappeared without a trace, then appeared again without explanation.

“Levinas spoke of his horror when one night hearing a rapping upon the door, he found [on his doorstep] a frail waif, slender, who hadn’t eaten for three days and demanded a place to spend the night. This was P. Shushani. One of those Jews who were once known as luftmenshen.”

In such a way Emmanuel Levinas caught the spirit of the Lithuanian yeshivot in France. And that which was called the foundation of Judaism in those yeshivot, studying the texts, first and foremost the primary sources, the Talmud. One of the best biographers of the Vilna Gaon, Eliyahu Stern (“The Genius: Elijah of Vilna and the Making of Modern Judaism”), says the catalyst which determined and fortified the importance of the textual in Judaism, the importance of Talmud study without the method of intellectual acrobatics prevailing until then (called pilpul) whose goal was to demonstrate that any contradiction between authoritative opinions are resolved in such a way that there will appear no contradiction, thus voiding the extremely important and significant for Judaic tradition discussions, disagreements and differences of opinion, was the image of the genius of the Vilna Gaon and legends about him, portraying him as a lone outsider, a self-taught genius, immersed in texts, studying them, learning them by heart, able to visualize in his mind entire volumes, to read by heart from beginning to end and emphasizing the importance of returning to deep study of the Talmud, and also renewing methods of study.

In this respect, Levinas was, although distantly, nonetheless a student of the Vilna Gaon, who in his essays on different questions and topical issues in Judaism underlined Torah study, the intellectual relationship with the sacred, counterposing the Eliadesque explanation of the relationship with the sacred against the heady brew of the hierophanies enveloping the mind of the human individual. And just as the Vilna Gaon did, he stressed studying the texts themselves, intensively “rubbing” them, like a foot against a foot, until blood appears, and blowing continuously upon the embers of coal, until open flame appears. These are metaphors he adopted from rabbinic tradition, in memory of the Vilna Gaon’s follower Haim of Volozhin. The Gaon himself, according to oral tradition, held to the position he should understand and exegete the texts himself, through his own faculties, without recourse to explanations received through revelation or dream.

Solomon Malka talks about Levinas’s proximity to the founder of the Lithuanian Mussar movement, Israel Salanter. Mussar, the literature discussing moral and general world-view issues in Judaism, was not studied at traditional houses of learning. Mussar books were popular and aimed mainly at the general public, especially women, who didn’t have the opportunity to study either at the midrash or yeshiva. But, as one scholar, Moshe Rosman, has pointed out, the popular Mussar literature was mostly written in Eastern Europe, and the books were published as bilingual editions, in Yiddish and Hebrew. The Mussar tradition in Lithuania stretches back to the 17th century, to the birth in Vilnius of Tzvi Hirsh Koidanover (1658-1712), who wrote Kav Hayashar (which could be translated as “The True/Honest Measure”) about the importance of improving moral qualities and living in tune with the Torah. The idea of the true (or honest) measure (by which the individual must learn to measure himself and understand himself) is repeated in different ways and expanded by the Vilna Gaon, his followers and the followers of his followers until Salanter himself and his followers and followers of his followers, who introduced the study of Mussar books and introspection exercises at yeshiva. Of course Levinas’s conception of ethics hardly adopted the basic ideas and practices of Lithuanian Mussar teachings (at least not directly), although there are correlations between them. Also concerning the concept of responsibility, which Vilna Gaon follower Haim of Volozhin taught, although in the foreword to the French translation of his book “Nefesh Hakhayim” written by Levinas he admits it is very important to him. Nonetheless Levinas attempted to “translate” both the ethical principles and the associated idea of responsibility into a universal philosophical language, to universalize it, thus leaving in one way or another traces of Judaism (whether it be Lithuanian or not is perhaps not so important in this case) in his philosophy.