Hello, Frau Finkelstein. You’ll forgive me if I continue to call you that, the way it’s written here, Frau Finkelstein? Thank you.

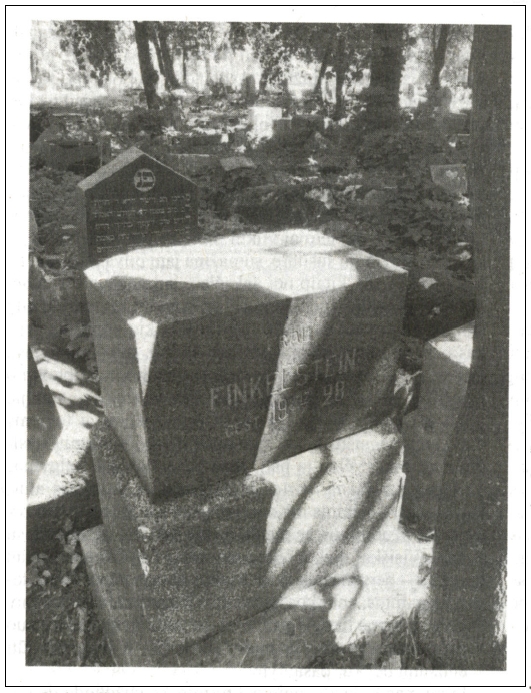

Don’t be angry, Frau Finkelstein, that it’s happening like this. It just turned out that way. By the way, why did they record you this way here, in the Jewish cemetery in Kaunas, not in Hebrew but in Roman characters, and as if that weren’t enough, why did they add “frau?” Was your husband German, Frau Finkelstein? Well, OK, fine, I know it’s none of my business. It’s just interesting, you know–you don’t even meet such a frau in the Jewish cemeteries in Lithuania. It’s too bad there’s no photograph of you. I guess there probably used to be. All that remains of you, Frau Finkelstein, is part of a headstone, the top portion of which is probably now part of some stairway or maybe a card table–black marble, candle flame, a glass of red wine, a deck of cards and the queen of spades, instead of your photograph, and they are playing poker there, which is at least an intellectual game, not some kind of “go fish.” … What? You say that’s cynical? Do you really believe so, Frau Finkelstein? God protect us, this is no cynicism, Frau Finkelstein. What does it say here on your remains–October 17, 1928. Hold on for a second, Frau Finkelstein, I want to check my mobile to see which day of the week that was.

Here it is, found it. You died on a Wednesday. So you were buried on Thursday. There were likely many relatives at the funeral, Frau Finkelstein. How many, you ask? Ooo. There aren’t that many Jews in the entire city now, and you said I’m cynical because of the top of the headstone/card table/stairs. The day before yesterday I was at an antique dealer’s and I saw a lapel pendant with a Hebrew inscription, made of silver–is it yours? I’m not making sense–if it were yours, you wouldn’t be buried here, you’d be in some pit by the side of a road. Then it might have been yours. What’s that? How much were they asking? Not much, a hundred and twenty euros, so that I’d stop by more often, they said. They said they sold what they called a rolling pin with a Torah two weeks ago, but it was actually a bit burnt. They said they often have the items from murdered people, and I should come by more often.

You’re lucky, Frau Finkelstein. You’re really lucky. Probably you don’t care now in your current completely broken state, but in the best of circumstances thirteen years after your death you would have been shot anyway at the Fourth, Seventh or Ninth Fort. Or right in your yard, pop, and that’s all, folks. Maybe it seems to you, Frau Finkelstein, somehow undignified, to stand broken without a top in a somewhat renovated cemetery in the middle of the city. That’s only how it seems. Something remains of you, Frau Finkelstein. And furthermore, there was no need to replace inscriptions after the Russians such as “to the victims, Soviet citizens”–you at least remain as you were when died until now, Frau Finkelstein, as the true, proud Frau Finkelstein. But the other ones had to get new inscriptions. As the new winds allowed. Of course the Soviet cement remains in place in many cases, those new winds of change somehow slackened off quickly. Who made your gravestone, Frau Finkelstein? I see it was made by expert craftsmen; the top could be broken off with a sledgehammer, but here, this pediment remains. And the letters have endured well. This is no Soviet “slap-slap-plop, it’s finished” for you. You can be proud, Frau Finkelstein.

Don’t be angry that I’m standing here, I will just speak with you a little while longer and I’ll be on my way, but you will stay here, broken but unbowed, right, Frau Finkelstein? Jawohl? You have been inventoried, counted, listed in a catalog and photographed from different sides. We have collected the trash from around you, Frau Finkelstein, needles, plastic beer bottles, broken glass, rags, it is clean now, it is shiny, the ordnung is plain to see.

I just wanted to say, Frau Finkelstein, that’s I’m still uncomfortable around you. That’s why I’m speaking with you here now, I would like it be a little bit different here, with you, and at the Seventh Fort in Kaunas. It’s just that there’re no names there. There’s no way to get to know anyone, to introduce yourself. It’s somehow depersonalized. But it feels a great deal warmer with you, Frau Finkelstein. What’s that you say? Oh, of course, you have family in Israel and at the Ninth Fort. What can we do, Frau Finkelstein, that our relatives are either there, or there? More here in Lithuania than in Israel, I would say. Yes, of course, I will pass your regards on, Frau Finkelstein, as soon as I’m there. You’re not the only one to ask.

Excuse me, Frau Finkelstein, I must go. I am grateful to you. What for? It’s strange, it’s just that now I know October 17, 1928 was a Wednesday. That Wednesday in October the Kaunas Jewish cemetery was still working.

Good-bye, Frau Finkelstein, auf Wiedersehen. Oh, wait. Could I take a photo of you? As a keepsake, so to speak? No, stop, regardless of age, regardless of our…

You look wonderful, Frau Finkelstein. Adieu.

Sergejus Kanovičius

Inscription on headstone:

Frau Finkelstein gest. 1928 X 17.

Photograph by author