This year marks the 125th anniversary of the birth of famous Litvak poet Osip Mandelshtam. At the LJC’s Mini Limmud conference held in November, one of the lectures was dedicated to the work of the famous poet. The lecture was by Ellena Suodienė, who is the author of 16 books of poetry and defended her doctoral thesis on the Russian poetry of Marina Tsvetaeva. Suodienė was awarded the Golden Quill diploma of the European Arts and Literature Institute and taught at the Kaunas Liberal Arts Faculty of Vilnius University until the year 2000. She published three books of poetry while she was teaching. She is the currently the hostess of the Nadezhda Russian Meeting Club in Kaunas. Suodienė has dedicated much of her time and research to the life and work of Osip Mandelstam and even wrote a poem about him.

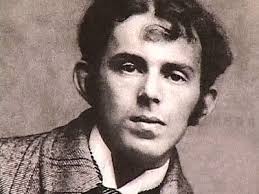

On the 125th anniversary of his birth we are again reminded Osip Mandelstam is one of the most famous Litvaks on the world stage. Many remember him as a brilliant poet who suffered under the persecution of the Stalin regime. Suodienė calls him a martyr to poetry.

His family roots are in Lithuania. Osip Mandelstam is a member of a Litvak family dynasty of great minds which includes many famous people. His family on both his mother’s and father’s sides comes from Lithuania. The Mandelstams come from the Lithuanian town of Žagarė where they lived since the 19th century. His mother’s family, the Verblovskis, lived in Jurbarkas and later moved to Vilnius. The Mandelstam family belonged to the merchant class. Häckel (or Emil) Manelstam, the son of Benjamin, was Osip’s father. The mother was Flora. The family lived in Kaunas, after 1891 in Warsaw, and n 1894 they moved to St. Petersburg, Russia. Osip was born in Warsaw and was baptized at a Lutheran church and remained apart from Judaism, which seems to indicate he didn’t feel comfortable living as a Jew. He lived a secular lifestyle in any case.

The writer and poet Tomas Venclova tells of an episode in Mandelstam’s life whe Stalin was in power and Mandelstam was being persecuted. Independent Lithuania’s ambassador to Russia at that time was the poet J. Baltrušaitis, who proposed Mandelstam remove himself and come to live in free Lithuania, and even offered to help obtain the visa, but Mandelstam turned down his offer. The poet’s life was extinguished by Stalin’s repression.

Mandelstam considered himself a poet of St. Petersburg. He wrote much about his views in childhood in the Russian language, although it wasn’t his native tongue. His mother was highly cultured and knew Russian well, and helped her son overcome the language barrier to such an extent that he become one of Russia’s most famous poets, writing in perfect Russian.

Dr. Suodienė calls Mandelstam’s poetry multilayered and says he was always creating new layers, with entire worlds he had created passing by unexplored, and that he contradicted himself. When he got into literature in his youth, no one recognized him, and the poet elite of the period rejected his untraditional style. For many his poetry seemed like a riddle. Although it is said each poet invents his own language, the path to achieving this was a hard one for him. As he wrote: “What pain looking for the word.”

The symbolists didn’t accept him. Only his acquaintance with the Russian poet Nikolai Gumilyev provided him sufficient impulse to issue his first book. Until the book, the poet had felt extreme loneliness, but afterwards he became a member of the poets’ guild, an acmeist. The proponents of acmeism rejected symbolism and mysticism in favor of presenting the fullness of life, portraying everyday scenes and phenomena. Gumilyev even wanted to turn the poets’ guild into a parliament of poets where each poet would be able to present and explain his views. Gumilyev published his article “Symbolism’s Legacy and Acmeism” during this period.

Mandelstam was Tomas Venclova’s favorite poet in the latter’s youth. He even visited the poet’s widow Nadezhda in Voronezh and after getting to know her called her a holy woman for saving her husband’s poetry when he was taken off to the gulag. She knew his poems by heart and her recitations preserved his poetic legacy. Venclova translated them to Lithuanian and they were published in the magazine Nemunas in 1967, a time when Osip Mandelstam’s poetry was still all but banned.