by Geoff Vasil

Rūta Vanagaitė presented her new book, Mūsiškiai [Our Own People], about Lithuanian Nazi collaborators, Holocaust complicity, Jewish victims and contemporary attempts to wriggle out of it to a packed room mainly filled with Lithuanian reporters Wednesday morning.

Rūta Vanagaitė (courtesy National Geographic Channel)

The venue was extremely strange: a small cafe called Submarine. Vanagaitė chose the location as the site where the murderous Ypatingasis būrys unit [Special Unit, often called simply Ypatingasis or Ypatingas in Holocaust literature in English] had their headquarters during the Holocaust. Vanagaitė said she would lead the audience up to the second floor after the book presentation to the main offices where Ypatingasis once planned the mass murder of the Jews of the region.

Submarine, Vilniaus street no. 37 (photo courtesy delfi.lt)

The cramped cafe had the main space in front of a large-screen television and speakers’ microphones reserved for press, so that most of the public–mainly Lithuanians but including a few members of the Jewish community as well–were effectively marginalized and forced to peek and peer around corners to catch site of what was going on.

Vanagaitė’s intentional media circus paid large dividends, though: almost immediately following the event the Lithuanian press including national radio and the news webpage Delfi provided unmediated coverage of the speakers and presentation.

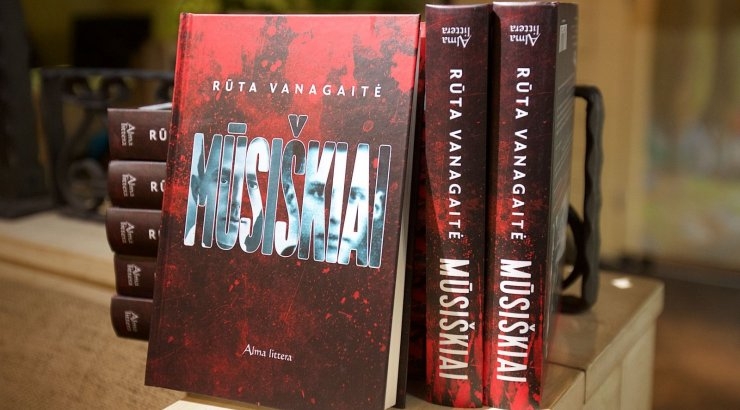

A pile of books at the event. (photo courtesy delfi.lt)

Tomas Šernas, a priest and hero of modern Lithuanian independence, arrived by wheelchair and spoke first. Šernas was a Lithuanian customs officer and is the only survivor of the Medininkai mass shooting on July 31, 1991. He survived a point-blank shot to his head. After extensive medical treatment and rehabilitation, Šernas was graduated from theological studies at Klaipėda University and joined the Reformed churches as a parson of the Vilnius parish. In 2010, he was elected for a three-year term as the General Superintendent of the Evangelical Reformed Church of Lithuania.

In his speech Šernas shared some simple but essential observations about the need for Lithuanians to own up to the Holocaust.

Efraim Zuroff, director of the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Jerusalem and now director of SWC for Central and Eastern Europe as well, faced down a field of television cameras and audio recorders to say how surprised he was when Vanagaitė originally told him she had Holocaust perpetrators among her relatives. He said her idea of traveling around Lithuania together to visit mass murder sites struck all the right chords for him: Lithuanians taking responsibility for their history. He also said he hadn’t expected to ever be surprised again after visiting Auschwitz and the other death camps in Poland, but was nonetheless shocked by what the duo learned as they performed their itinerary last summer. He also said he was outnumbered by priests at the event, and wasn’t interested in talking about religion, only justice.

Simon Wiesenthal Center in Jerusalem director and campaigner for Holocaust justice Efraim Zuroff

Following Zuroff a young Catholic priest spoke and tried to connect Old Testament motifs with the Holocaust, comparing the blood of the innocents which saved the firstborns in Egypt from the Angel of Death with the innocent blood spilled in Lithuania. He also dismissed the idea of restitution as unnecessary, insisting instead a moral reconciliation was needed. He said both he as the victim and the man standing above him at the edge of the pit pointing a rifle down at him–the perpetrator–were both equally victims. He also said only God could sort out all this nonsense, nonsense meaning Holocaust. While he referred to recent statements against anti-Semitism and in favor of Judaeo-Christian reconciliation by Pope Francis, he failed to mention the Church’s complicity in the Holocaust in Lithuania or anywhere else.

The choice of a Protestant and a Catholic priest at the event wasn’t accidental: Vanagaitė enlisted both clerics to write short pieces for her new book. The choice evidently also deeply affected the mainly Lithuanian audience, who gave their rapt attention to both speeches.

Vanagaitė presented a short video detailing the scope and some of the basic facts of the Holocaust in Lithuania. She invited the audience outside after the event to the alleyway leading back into a courtyard which for many years was surrounded by a police station and a passport issuance office. In the alleyway local children sang a moving song in Hebrew, after which Efraim Zuroff read a prayer for the dead. Vanagaitė then invited the audience to ascend to the second story of the building of the alley where she said the Ypatingasis biūras once had their headquarters in Vilnius. Movers were removing shelving from a neighboring room as perhaps fifty people crammed into a small and cold room, where a young man read an excerpt–a real testimony Vanagaitė discovered–from the book.

Vanagaitė’s book consists of two parts: testimonies, diary entries and archival information about the Holocaust in Lithuania largely found in other sources and from Lithuanian archives, and her and Zuroff’s trip around Lithuania last summer to visit mass murder sites, interview eye-witnesses and learn the local lore about the Jews who once lived there and how they were murdered. In some cases Zuroff and Vanagaitė were unable to determine exact locations or discover commemorative markers which are supposed to mark them.

Vanagaitė spoke about the fear she encountered in trying to publish her book. There were legal uncertainties in places, but mainly fear and reluctance on the part of many to see the work go forward. The publisher Alma Littera of Vilnius bravely went forward with the project, in any event.

Vanagaitė’s book presentation was a massive failure as an event for the public. It was a media circus and the public were of secondary consideration in terms of space. As a media event it was first rate and had the desired effect. Her book–and I’ve read the entire thing because I translated it into English for her as she wrote it, chapter by chapter–is very well written, extremely interesting and ultimately very honest about the part Lithuanians played in murdering their Jewish neighbors. It’s just what was needed: Lithuanians telling it like it is, instead of Jews, instead of the Lithuanian Jewish Community, instead of outside agencies and interests. Her take on the facts is very down to earth, and while perhaps it isn’t overly scholastic, it gets to the root of the problem in a way those who have sponsored muckraking and scandal have been unable to achieve for two and a half decades of Lithuanian independence. It will be interesting to see how Lithuanian society deals with the book and the topics it raises, and likewise interesting to see how Holocaust scholarship receives it, if the English translation is ever published. It doesn’t say much that is new–it’s what the outside world mainly already knows–but it says it in a Lithuanian voice, and with real style.