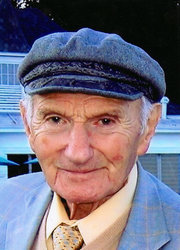

Joel Elkes, whose father was Dr. Elkhanan Elkes, the reluctant chairman of the Kaunas ghetto Ältestenrat, or council of elders, died at the age of 101 on October 30 in Sarasota, Florida. Joel Elkes made major contributions to modern psychiatry. His wife Sally Lucke Elkes reported the cause of death was kidney failure.

Dr. Joel Elkes helped shape

treatment for schizophrenia.

Photo: New York Times

Joel Elkes, Who Cast Light on Brain Chemistry and Behavior, Dies at 101

by Benedict Careynov

December 17, 2015

Dr. Joel Elkes, who published the first scientific trial of a medication for schizophrenia and became a foundational figure in modern psychiatry by describing a framework for understanding how brain chemistry shapes behavior, died on October 30 in Sarasota, Fla. He was 101.

His wife, Sally Lucke Elkes, said the cause was kidney failure.

Dr. Elkes (pronounced EL-kess) was a young researcher in England when a pair of French doctors reported that a new antihistamine, called chlorpromazine but better known under the trade-name Thorazine, had a remarkably calming effect on people with schizophrenia. He and his first wife, Dr. Charmian Elkes, both then at the University of Birmingham in England, tested the drug using a placebo pill control in people with schizophrenia and related conditions.

The study was “blind,” meaning neither the doctors nor the nurses delivering the treatment knew who got the drug and who received a placebo. In the September 4, 1954, issue of the British Medical Journal, the couple concluded that the drug “may have its place” in the management of psychosis, the signature symptom of schizophrenia.

The trial was seminal in two respects. Its design, blinding people to treatment and comparing to a placebo, has become standard in such drug trials. And chlorpromazine became the first-line treatment for psychotic symptoms, helping to end the practice of lobotomy–particularly common in the United States–in which tissue in the frontal lobes is blindly destroyed to “calm” people with mental disorders.

The dozen or so drugs developed since then for psychosis are all based, at some level, on the molecular properties of chlorpromazine.

Dr. Elkes drew on this and other work to formulate a theory of brain function, arguing that chemical messengers are central to driving behavior and that those messengers operate differently in different neural regions, in the same way dialects are better understood in some places than in others.

“At the time, people thought that transmission in the brain was mainly physical, that it was electricity,” Dr. Thomas Ban, a professor emeritus of psychiatry at Vanderbilt University, said in an interview. “He actually foresaw what we later learned” from neuroscience.

Scientists have since isolated a number of so-called neurotransmitters, such as serotonin and dopamine, which circulate more heavily in some areas of the brain than others. The details of how such brain chemicals alter behavior are still largely unknown, but most of the psychiatric drugs doctors prescribe today target the activity of one or more of these chemical messengers.

“Joel Elkes introduced the modern paradigm for psychiatry,” said Dr. James Harris, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral science at Johns Hopkins University, “and it was a unique blend of neuroscience and humanity.”

Joel Elkes was born on November 12, 1913, in Königsberg (now the Russian city of Kaliningrad) in what was then eastern Prussia to Miriam Albin and Elkhanan Elkes. His father, a prominent doctor, became a medical officer in the Russian Army during World War I and the Russian Revolution, after which the family settled in Kovno (now Kaunas), then the capital of the newly-formed Lithuanian Republic.

Joel Elkes graduated with high honors from a Jewish high school and enrolled in medical studies at St. Mary’s Hospital in London in 1930.

He was completing his medical studies when World War II cut him off from family support. In 1941 the Nazis herded Kovno’s Jews into a ghetto; the group chose Elkhanan Elkes as its leader, and he worked for two years to protect them. But in 1944 the Germans attacked the ghetto and shipped survivors to a concentration camp, including his father and other family members. His father died there, along with three uncles, an aunt, and nieces and nephews.

Dr. Elkes cited his parents as examples of humane leadership throughout his career, which took off in the wake of the war. In 1951, he was appointed chairman of the newly formed Department of Experimental Psychiatry at Birmingham.

In 1957 he was invited to establish a similar program for the National Institute of Mental Health in Washington, D. C. There, working at the affiliated St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in the city, he published a series of papers on brain chemistry.

He also established a culture–rare today, when there is so much specialization–in which researchers mixed with the people who were subjects in their experiments.

“There was, always and always, the presence of the patient,” Dr. Elkes wrote. “You go to the canteen for lunch, and there’s a patient with schizophrenia hallucinating under a tree. You’re never very far away from the problem that brought you here.”

He left the institute in 1963 to become the chairman of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins. He left that post in 1974 and later took positions at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, and the University of Louisville.

Along the way, Dr. Elkes helped form several professional organizations to anchor the study of brain chemistry and behavior as a science in its own right; among them the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology and the National Institute for Psychobiology, housed at Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

Dr. Elkes’s first marriage ended in divorce. His second wife, Josephine Rhodes, died.

Besides his wife, he is survived by a daughter, Anna Elkes Parris, and a granddaughter, Laura Parris.

Dr. Elkes won most of his field’s major awards and published some 40 scientific papers as well as more than a dozen influential book chapters.

He was both formidable and personable, those who knew him said–an enthusiastic presence with a touch of old-world eccentricity.

“He had the biggest desk and the smallest pipe I’d ever seen,” said Dr. Floyd Bloom, professor emeritus at the Scripps Research Institute in San Diego. “The first time I met him, he was sitting behind that desk, twirling a pipe the size of your thumb, just commenting on absolutely everything with his English accent. It was exciting.”