Aut. Geoff Vasil

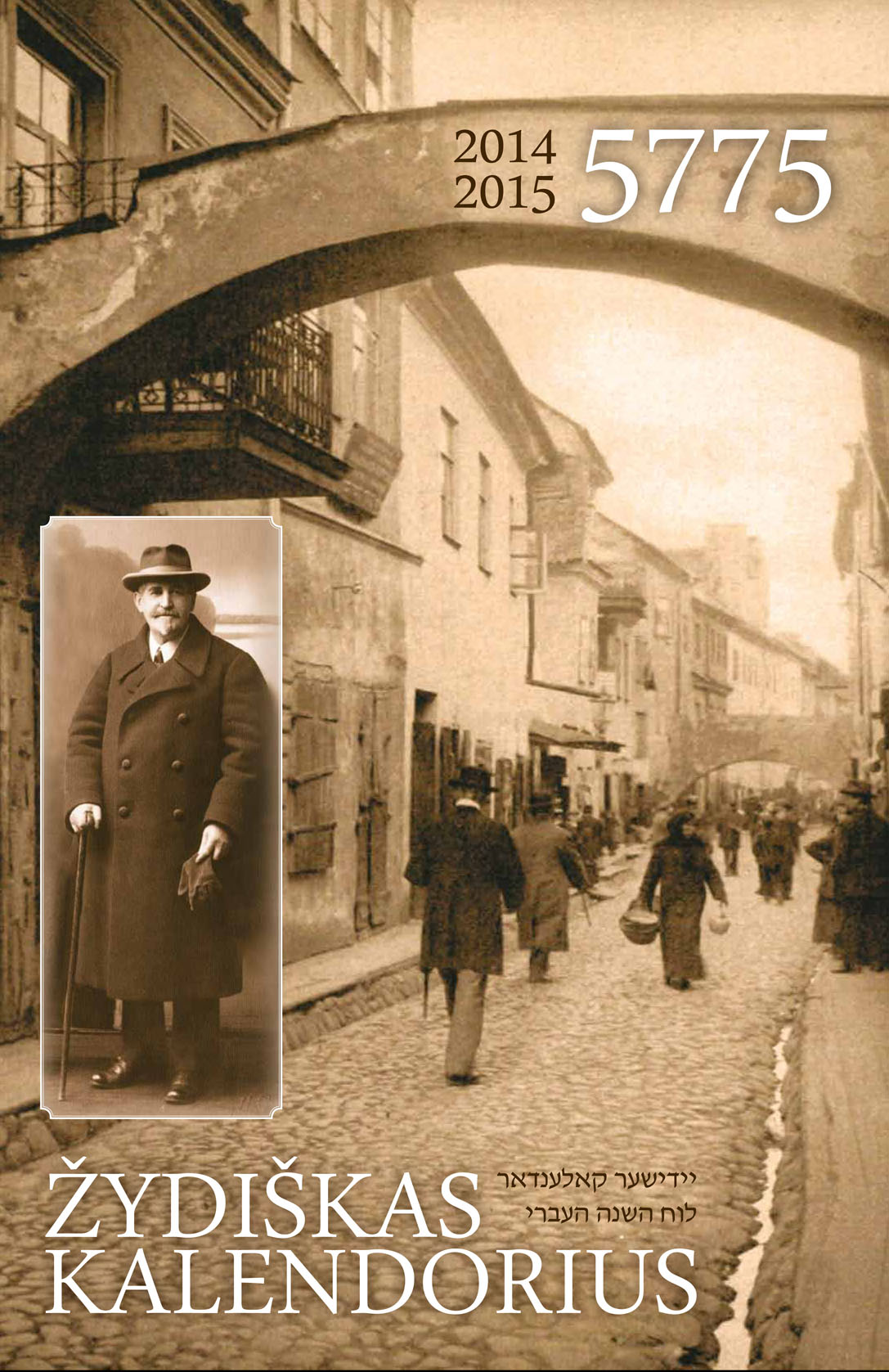

For a number of years now the Lithuanian Jewish Community (LJC) and the Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) have produced Jewish calendars distributed free to community members and friends during the Jewish New Year season. Each edition of the calendar features a central theme. This year, 5775, the theme chosen was Lithuanian Jewish contributions to medicine. The choice was not random.

Over the past five or ten years a number of Lithuanian cultural figures have rediscovered the fact that a beloved literary character was based on a real Jewish man who lived and worked in Vilna. Korney Chukovsky’s stories centered around the figure of Dr. Aibolit (Russian, pronounced áy-balít for ‘Ay, it hurts!’), called Daktaras Aiskauda in Lithuanian (Aiskauda also means ‘Ay, it hurts!’ in Lithuanian), and were roughly modeled on the character of his friend Tsemakh Shabad (1864-1935), the renowned Vilna children’s doctor and all-around humanitarian and cultural leader.

The Aibolit stories were loosely based on the English-language Doctor Dolittle books by British author Hugh Lofting, but don’t tell that to anyone who grew up in the Soviet Union. If you do, you’re likely to start a row every bit as passionate as the on-going cultural conflict over whether Vinny-Pukh is really based on Winnie-the-Pooh, or whether the phrase “to fall into the hands of the living God is a fearful thing” is an ancient Ukrainian peasant saying or actually comes from Hebrews 10:31 in the New Testament (or was it really Robert W. Chambers with his “King in Yellow” cycle who “repopularized” it?). Ultimately, possession is nine-tenths of the law and claims to cultural authorship are a sincere form of flattery. But does it work in reverse? Is it possible to work backwards from the fictional character of Aibolit in the children’s stories to the real, living man?

In 2007 Shabad and his Aibolit doppelganger were commemorated in Vilna with a statue of presumably one of them leaning down towards a little girl cradling a cat in her arms. The statue is metal. There is a squat, brown granite pyramid shape next to its base with four inscriptions in four languages. Each inscription says something different, although one senses they were intended to be the same originally. One feels different communities rallying around that very small pyramid, preparing to vie for ownership of its lofty apex rising several inches above the sidewalk, but not sure the prize is worth the effort and content to occupy each their own designated linguistic area for the time being under the pyramid’s great shadow. Whatever the separate inscriptions tell us about Shabad’s legacy, there are no skateboard marks on the pyramid, which speaks to some kind of respect which goes beyond formal declarations made on solemn occasions.

Shabad and the pyramid, although small, do have a kind of symbolic resonance. Vilna Jewry included a proportionally large intellectual elite before WWII. That’s not to say Vilna Jews were elitist, although certainly some might have been, but Jews in Lithuania and in Vilna specifically occupied important positions in the social hierarchy, both of the wider European Jewish world and locally, domestically as they say nowadays. Shabad didn’t emerge fully formed from the brow of Zeus and did not operate in a vacuum. Litvaks have been central to Lithuanian medical history all along, longer than there has been a Lithuanian Republic per se, and Shabad is just the tip, albeit prominent, of that deep iceberg. As the new calendar notes, three Jewish researchers originally from Lithuania were awarded Nobel prizes in medicine and chemistry. The chemistry prize went to Aaron Klug for his work in developing electron microscope techniques in 1982, so it was essentially for medicine as well.

There have been no “ethnically Lithuanian” Nobel prize recipients. The closest the country can claim, if Jews are excluded as they usually are from such discussions, is Vilna Pole Czeslaw Milosz, who won the prize for literature in 1980 for his 1951 book “The Captive Mind,” which was decidedly NOT literature, and the prize was, not for the first nor for the last time, awarded based on politics. It was an anti-Soviet book, basically intended to “debunk” Soviet Communist training and education as worthless. If ever a work selected by the Nobel committee had an expiry date, it is this one.

Litvak doctors and medical researchers, on the other hand, made lasting if little-known contributions to medicine inside and outside of Lithuania. There is a telling list at the end of the calendar, with the caption: “In 1922, 138 of the 391 doctors in Lithuania were of Jewish ethnicity.” What follows is a list of names of all 138.

The calendar is graphically beautiful, and uses a subtle mix of subdued colors in combination with period photographs and texts, mainly in Lithuanian but with a summary in English towards the end. The reverse of each calendar page contains more exhaustive information about the person or agency featured for that month. The calendar proper is the usual format of the Jewish months superimposed onto the modern calendar with Jewish holidays and local times for Sabbath indicated.

Perhaps the figure of Tsemakh Shabad, Dr. Aibolit, is the appropriate introduction to pre-war Vilna for outsiders, because he was that combination, that ideal of being part of the elite in terms of knowledge and competence, but never elitist, never failing to heed the call of the needy and never abandoning that broad highway called humanity for some perceived greater cause. All who ever knew him said he was a genuinely good man. Good, knowledgeable, competent and human, qualities which define the pre-war Litvak community, qualities to which the current community continues to aspire in our new century.