Indiana University Press 2014

416 Pages

Review by Jack Fischel

This unusual book was composed by members of the Jewish police force who served in the Kovno Ghetto from August 1941 until March 1944, when the Nazis murdered its leadership. The writers of this riveting document were determined to provide a truly balanced history of the Jewish police force as it interacted with ghetto inhabitants, the Nazi occupiers, and their Lithuanian auxiliaries—virulent anti-Semites whose violence against Jews shocked even their German masters. The chronicle is also a refutation of Raul Hilberg and Hannah Arendt, whose works were highly critical of the Jewish councils and the Jewish police leadership in the ghettos. One distinguished Holocaust historians, Samuel Kassow, notes in his introduction to the book that “the chronicle… serves as a caution not to rush to blanket judgments of the Jewish police—or of the Jewish ghetto leadership. Each ghetto had its own context and circumstances.”

True, the Jewish council in Kovno was very different than Rumkowski’s leadership in the Lodz ghetto. Given that the Nazis established more than 15,000 concentration camps in German-occupied Europe, Kassow is on firm ground when he accuses Hannah Arendt of being simplistic when she wrote in Eichmann in Jerusalem that “had the Jews refused to establish Jewish councils…and simply scattered, many would have died, but far fewer than six million would have been murdered by the Germans.” Elsewhere, Arendt wrote that “To a Jew, this role of the Jewish leaders in the destruction of their own people is undoubtedly the darkest page in the whole dark story.” Kassow argues, as evidenced in the Jewish police history, that they had to function “within a zone of choice-less choices.”

These chronicles offer a rare glimpse into the complex situation faced by the Kovno Ghetto leadership: caught between the brutality of their Lithuanian and German captors, the Jewish policemen attempted to mediate between the demands of the occupiers and the anger of the ghetto population. The book describes the arbitrary manner of the Germans wherein, at a moment’s notice, the Nazis demanded that the Jewish council round up Jews for deportation to the death camps. Similarly, the authors illustrate the cruelty involved in the German demands for Jewish labor with the alternative of death for shirkers.

The secret history of the Jewish police is both a defense of their actions as well as a criticism of Jewish leaders who took advantage of their positions of authority. The chronicle captures an environment in which the irrational hatred of Jews by the native Lithuanian population and the organized Nazi killing machine made it virtually impossible for Jews to avoid the wanton death desired by their enemies. The Jewish councils and the Jewish police bought time for the Jews imprisoned in the ghetto, always hoping that either the Messiah or the Soviets would deliver them from the inevitable death that they faced on a daily basis

March 28, 2014

Q&A with Samuel Schalkowsky on “The Clandestine History of the Kovno Jewish Ghetto Police”

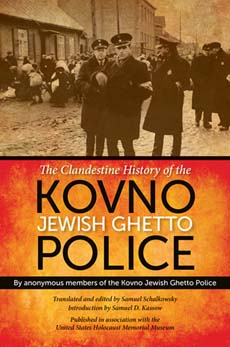

A new book we published in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) uncovers a history from World War II that remained hidden for several years. “The Clandestine History of the Kovno Jewish Ghetto Police” tells the dramatic and complicated story of a police force that had to serve two masters: the Jewish population of the Kovno ghetto in Lithuania and its German occupiers. As a result, the Kovno Jewish ghetto police walked a fine line between helping Jews survive and meeting Nazi orders

In 1942 and 1943 some of its members secretly composed a history and buried it in tin boxes. This history remained buried until 1964 when it was accidentally discovered during the bulldozing of the former ghetto. Soviet authorities suppressed the publication of this and other Jewish documents for several more years until Lithuania achieved its independence in the 1990s.

The USHMM obtained a microfilm copy of the Kovno Jewish ghetto police history collection in 1998. USHMM volunteer Samuel Schalkowsky was assigned to work with these documents because he was a former inmate of the Kovno ghetto. This work eventually led him to become the translator and editor of “The Clandestine History of the Kovno Jewish Ghetto Police”. In this interview, he shares his experiences living in the ghetto and working on this book.

Was it difficult for you to work on this book since you were an inmate of the Kovno ghetto?

Not particularly. The events dealt with in the book took place some 70 years ago and emotional reactions to them are counter-balanced by a strong motivation to learn more details as they related to me and, particularly, to publicize conditions of ghetto life and their effect on its inmates.

What do we know about the authors of the Kovno Jewish ghetto police history and why they wrote it?

The manuscript states in the Introduction that “The creators of the history are themselves policemen…” and that their objective is to provide the future historians “sufficient verified material of the history of the Kovno Jews in the gruesome years of 1941, 1942…” Beyond that, very little is known, as the organizers and authors of the manuscript purposely maintained anonymity in order to allow for objectivity when writing about the leadership of the various ghetto organizations. As stated in the manuscript, they wanted to “try with all their might to preserve objectivity, to convey all experiences and events in their true light, as they actually occurred, without exaggerating or diminishing them.”

The history was written in Yiddish. Describe your approach to translating it for the English-speaking reader.

My principal concern in translating the Yiddish text was to provide a faithful rendition of both the factual content and the emotional overtones of the original text. I approached this by preserving the sentence order of the original to the extent possible while adapting a sentence structure more familiar to the English-speaking reader. Sometimes the sentence order of an entire paragraph had to be rearranged in order to convey the information and/or mood of the original. On other occasions, a number of short consecutive paragraphs dealing with the same topic had to be combined into one paragraph in order to maintain continuity of the narrative.

How did you feel about the police while living in the ghetto? Did your opinion of them change after you read their history?

I and my mother lived in the Kovno ghetto from its inception August 1941 until our deportation to the Riga ghetto early February 1942. Although I knew Michael Bramson, the initial deputy chief of the Jewish police—he was my teacher in high school only a few months earlier, I had no contact with him. The prudent approach to the police during this period was to avoid them whenever possible in order not to be taken by them to unfavorable work details, particularly to airport construction.

Early February 1942 my mother and I were taken by two Jewish policemen off a ghetto street to the assembly point for transfer to Riga. Bramson was there, in charge of the Jewish policemen guarding us. Although we were being assured that this transfer was indeed for work, we did not believe it, as no other transfer before this ever returned alive; there was evidence of them having been murdered at the Ninth Fort. I shouted in the direction of Bramson, in Yiddish: “I want to live.” There was no reaction and nothing was done to remove me and my mother from the group destined for Riga. I held this against Bramson for a long time, although it is quite likely that Bramson did not even hear me.

I learned from the description of the Riga action in the police history book that next to Bramson and his Jewish policemen were Nazi SS men waiting to march us to the railroad station for transport to Riga. A rescue attempt of anyone of the guarded Jews at this stage would have been quite unrealistic.

What new information did you learn from the Kovno Jewish ghetto police’s history?

I learned a lot more detail about events that affected me since the police history covers the period that I was there and the people I was involved with in considerable detail; for example, about my former high school teacher turned into deputy chief of police.

What do you hope readers will learn from this book?

I hope the reader will get a sense of the realities of life under constant threat of pain and death in a ghetto dominated by Nazi rule. Also, how individuals and the leadership of the Kovno Jewish community dealt with moral issues and their life and death consequences. Remembering the victims honors their life.