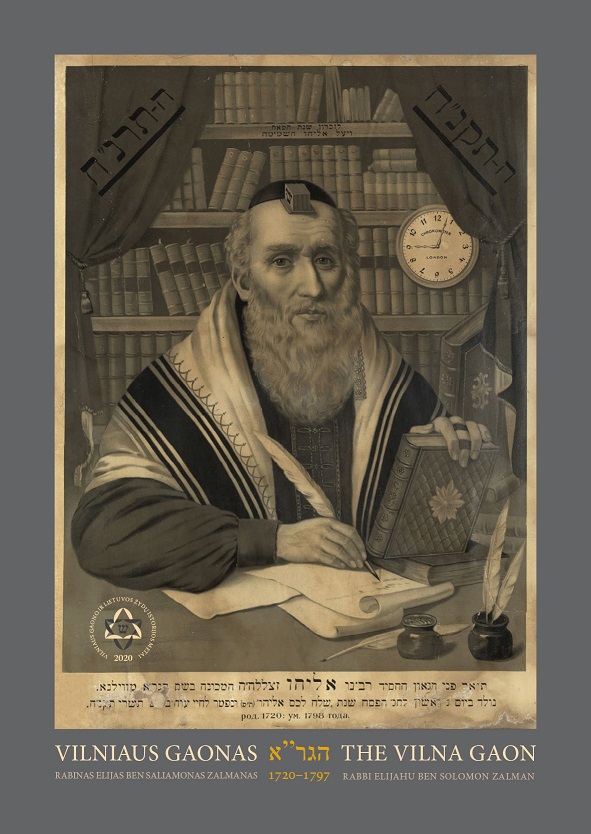

The Lithuanian parliament has proclaimed 2020 the Year of the Vilna Gaon, the 18th century scholar and cultural figure Eliyahu ben Solomon Zalman, and the Year of Litvak History. This anniversary has also been listed on UNESCO’s list of anniversaries for 2020 and 2021. On April 23 we mark the 300th birthday of the Vilna Gaon.

Scholars consider the Gaon the greated Talmudic scholar in Eastern European Jewish history. He is also the father of the rabbinical movement’s struggle against Hasidism and is considered the primary figure in rabbinical learning among Eastern European Jews. The Gaon and his followers, mitnagdim or misnagdim (literally “opponents,” i.e., of Hasidism) are sometimes called prophets of learning.

The Vilna Gaon had a deep interest in different branches of the exact sciences and his texts on geometry, astronomy and geography are often ascribed to the Haskalah, the Jewish enlightenment which arose in the 1770s in Central and Western Europe. Alan Nadler, professor emeritus of religious studies and formerly the director of a Jewish studies program in the USA, says the Gaon’s interest in secular subjects stimulated the expansion of many academic fields and the Gaon became a symbol of educated Judaism.

The picture of the Gaon as a remarkable and varied scholar and an unusually highly knowledgeable Lithuanian Jewish teacher for his time has not just survived to this day, but has been added to by his students and followers, especially by Hasidism’s rabbinical opponents, the misnagdim.

YIVO’s encyclopedia of Eastern European Jewry says the Vilna Gaon, often referred to by the Hebrew acronym GRA, for Gaon Rabbi Eliyahu, was a giant of the spirit and set an example for the generations; he was the a source of inspiration and the central figure in Litvak culture, according to YIVO.

Eliyahu ben Solomon Zalmas (1720-1797) was born to a family of rabbis and studied at heder, and studied Torah with his father. At the age of 7 he was sent to Keydan (Kėdainiai) to study under Rabbi Moshe Margolis (aka Margolies, Moshe ben Shimon Margalit). Soon after that he began studying independently, and at the age of 18 left Vilna (Vilnius) to “wander” among the Jewish communities of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Poland and Germany.

Returning to Vilna, Eliyahu ben Solomon Zalman retired to his home and concentrated on Torah study. The local Jewish community supported his research and he pursued the path of the scholar his entire life.

Writer and rabbi Elijah J. Schochet writes the Litvak nature and its distinctiveness is the legacy of the Vilna Gaon.

The small, impoverished Lithuanian Jewish community excelled much beyond fellow Jews from larger and more affluent countries. The community gave birth to great rabbinical scholars, highly-educated secular Jews, abundant publication of literature and all sorts of scholarly and cultural achievements.

The power of the Gaon’s teaching and his attitude towards learning had great influence on the yeshiva movement, as has been long recognized. There is no dispute the Gaon’s legacy helped make Vilna the center of Torah study by 1802.

Fifty years after the death of the Gaon, his main follower and spiritual successor Chaim of Volozhin (1749-1821) started the yeshiva in Volozhin, fulfilling the Gaon’s wishes, and incorporating many of his religious and pedagogical convictions.

There were many yeshivot in Lithuania along with the Mussar movement, a purely Lithuanian phenomenon. Although this came about fifty years after the death of the Vilna Gaon, the genealogy of this spiritual movements begins with him.

The first and most important principle was the supremacy of knowledge based on Torah study. Litvaks were completely convinced “knowledge makes a person a person and a Jew a Jew.” This is the direct inheritance from the Gaon which put Lithuania firmly on the path to becoming the seat of Torah study.

Rabbi Shochet writes how this led to the development of the stereotypical Litvak with his characteristic rationalism and intellectualism, love and pursuit of knowledge, mental discipline and independence of thought, retiring nature and emotional reserve, humility and individuality, ethical sensitivity and other traits.

The Gaon didn’t judge religiosity according to adherence to religious norms or the wearing of ritual clothing, but according to the degree of attention paid Torah study. “The only mitzva which rises above all other mitzvot is Torah study,” the Gaon is reputed to have said. He is reported to have believed each and every word of the Torah comprehended by the person was equal to all the mitzvot he had performed.

Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik of the renowned Soloveitchik dynasty of rabbinical scholars writes the Gaon didn’t waste time on hymns and praises, and believed knowledge of Torah was the holiest and most exalting service to God. Soloveitchik says the Gaon served God by explaining the secrets of halacha, the law, sorting out difficulties and solving the problems of the Talmud. Torah study was the sum of his aspirations and the basis for everything. Soloveitchik says the Gaon said “The Torah is for the soul of man as the rain is to the soil.”

At first glance the equating of Torah and rain appears simplistic. Nonetheless, the rain supports life, just as the Torah supports Jewish life.

The Gaon didn’t stop there with this teaching but delved much deeper. He warned just as the rain brings to life everything buried in the earth, both the fruitful crops and the noxious weeds, to too the Torah brings to life everything buried in the soul of man. If the man’s soul is noble, Torah study will only make it nobler, but if the soul is fallen, sinful and disordered, it will fall further and become more sinful through Torah study. The soul must be prepared for Torah study no less than the earth must be prepared for the rain, otherwise the ill-prepared and incorrectly educated mind will only distort the meaning of the Torah and desecrate its thought. The equation between Torah and rain continues in this vein. The message is clear: appropriate preparation is vital.

The Gaon believed preparation for Torah study began with a thorough acquaintance with the legal documents of the Talmud, and we can only begin to comprehend the great intellectual independence of the Gaon as evidenced in his halachik texts by bearing this in mind. The Gaon wasn’t so concerned with severity or dissolution as he was with the issue of whether the primary texts of the law were being interpreted correctly.

The Gaon emphasized the need for emotional tranquility in scholarship, the rational, intellectual ability to think rather than surrendering to or seeking religious ecstasy and emotional religious fellowship, which disturb and distract the presence of mind needed for Torah learning.

The rule in the Lithuanian yeshivot was to distinguish “purity of thought” and intellect from “the powers of the soul” so that what remained was the truth.

The Memory of the World program of UNESCO included the corpus of works by the Vilna Gaon on the Lithuanian National List in 2019.

Information collected from rabbinical and other sources.